Health care is the most serious domestic policy problem we have, and Medicare is the most important component of that problem. Every federal agency that has examined the issue has affirmed that we are on a dangerous, unsustainable spending path:

- According to the Medicare Trustees, by 2012 the deficits in Social Security and Medicare will require one out of every 10 income tax dollars.

- They will claim one in every four general revenue dollars by 2020 and almost one in two by 2030.

- Of the two programs, Medicare is by far the most burdensome — with an unfunded liability five times that of Social Security.

- Nor is this forecast the worst that can happen:

- The Congressional Budget Office notes that health care costs overall have been rising for many years at twice the rate of growth of our incomes.

- On the current path, health care spending (mainly Medicare and Medicaid) will crowd out every other activity of the federal government by midcentury.

There are three underlying reasons for this dilemma:

- Since Medicare beneficiaries are participating in a use-it-or-lose-it system, patients can realize benefits only by consuming more care; they receive no personal benefit from consuming care prudently and they bear no personal cost if they are wasteful.

- Since Medicare providers are trapped in a system in which they are paid predetermined fees for prescribed tasks, they have no financial incentives to improve outcomes, and physicians often receive less take-home pay if they provide low-cost, high-quality care.

- Since Medicare is funded on a pay-as-you-go basis, many of today’s taxpayers are not saving and investing to fund their own post-retirement care; thus, today’s young workers will receive benefits only if future workers are willing to pay exorbitantly high tax rates.

To address these three defects in the current system, we propose three fundamental Medicare reforms:

- Using a special type of Health Savings Account, beneficiaries would be able to manage at least one-fifth of their health care dollars (and up to 40 percent under the “Intermediate Model”) — thus keeping each dollar of wasteful spending they avoid and bearing the full cost of each dollar of waste they generate.

- Physicians would be free to repackage and reprice their services — thus profiting from innovations that lower costs and raise the quality of care.

- Workers (along with their employers) would save and invest 4 percent of payroll — eventually reaching the point where each generation of retirees pays for the bulk of its own post-retirement medical care.

These reforms would dramatically change incentives. Whether in their rôle as patient, provider or worker/saver, people would reap the benefits of socially beneficial behavior and incur the costs of socially undesirable behavior. Specifically, Medicare patients would have a direct financial interest in seeking out low-cost, high-quality care. Providers would have a direct financial interest in producing efficient, high-quality care. And workers/savers would have a financial interest in a long-term financing system that promotes efficient, high-quality care for generations to come.

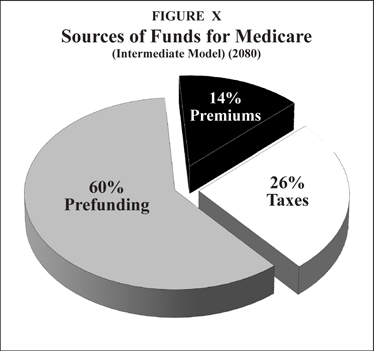

With assistance from Andrew J. Rettenmaier, an NCPA senior fellow, we have been able to simulate the long-term impact of some of these reforms. The bottom line: Under reasonable assumptions, we can reach the mid-21st century with seniors paying no more (as a share of the cost of the program) than the premiums they pay today and with a taxpayer burden (relative to national income) no greater than the burden today. Along the way, the structure of Medicare financing will be totally transformed:

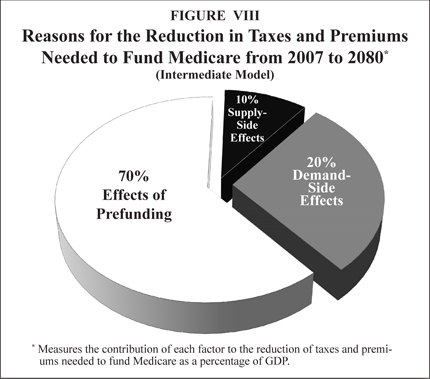

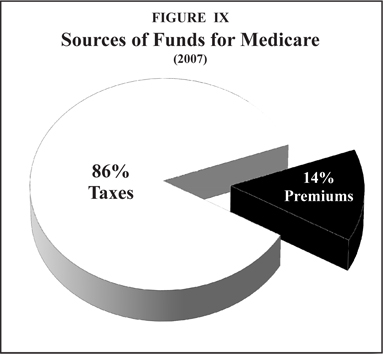

Whereas today, 86 percent of all Medicare spending is funded through taxes, by 2080, taxes will be needed for only one out of every four dollars of spending.

- Whereas there is no prefunding of Medicare today, 60 percent of all Medicare spending will eventually be funded through savings generated by beneficiaries during their working years.

- In terms of the impact of Medicare on the economy as a whole:

- With no reform, the size of the Medicare program will more than triple (relative to national income) over the next 75 years.

- With reform, Medicare will take no more of national income than it does today.

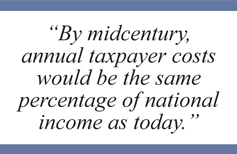

- Of the savings brought about by reform (Intermediate Model), 70 percent are due to the effects of prefunding, 20 percent are due to improved demand-side incentives and 10 percent are due to better supply-side incentives.

The most important domestic policy problem this country faces is health care. The most important component of that problem is Medicare. Forecasts by every federal agency that produces such simulations — the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the Social Security/Medicare Trustees, the General Accounting Office (GAO) — show that we are on a dangerous and unsustainable path. Indeed, the question is not: Will reform take place? The question is: How painful will reform have to be?

In what follows, we propose short-term and long-term reforms. Although these reforms are far from painless, they are far less burdensome than the cost of putting off reform many years into the future. This plan builds on a series of studies and detailed policy proposals by the National Center for Policy Analysis over the past 25 years that have analyzed prefunding the health expenses of the elderly.1

Here’s the bottom line: In return for making small sacrifices today, very realistic simulations show that we can reach midcentury — when today’s teenagers reach retirement age — with a Medicare system no more burdensome (relative to national income) than the program is today.

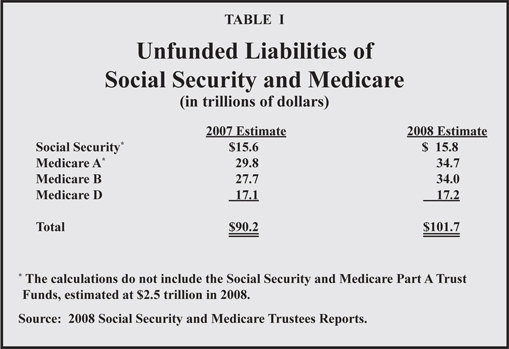

The Size of Unfunded Entitlement Debt. The 2008 Social Security and Medicare Trustees Reports show the combined unfunded liability of these two programs has reached $101.7 trillion in today’s dollars. [See Table I.] That is more than seven times the size of the U.S. economy and 10 times the size of the outstanding national debt. The unfunded liability is the difference between the benefits that have been promised to retirees and what will be collected in dedicated taxes and Medicare premiums. Although Social Security’s projected deficit has received the bulk of attention from politicians and the media, Medicare’s future liabilities are far more ominous. In fact, Medicare’s total unfunded liability is more than five times larger than that of Social Security.

Causes of the Problem. Medicare is in trouble for two reasons. First, health care spending has been growing at twice the rate of growth of national income for the past four decades and that trend shows no signs of abating. One doesn’t need a spreadsheet or a computer program to know that if this trend continues, health care will eventually crowd out every other form of consumption. Second, elderly entitlement programs are based on pay-as-you-go finance rather than a funded system in which each generation saves and invests and pays its own way. Pay-as-you-go means every dollar collected in Medicare payroll taxes is spent. Nothing is saved. Nothing is invested. The payroll taxes contributed by today’s workers pay the benefits of today’s retirees. Without reform, however, today’s workers will receive their retirement benefits only if the next generation of workers is willing to pay much higher taxes.

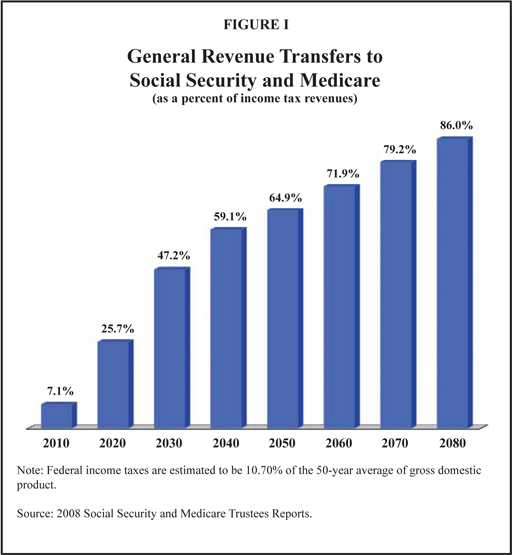

Effects on Federal Government Cash Flow Finances. Until recently, the effect of Social Security and Medicare on the rest of the federal government was relatively small. However, the combined deficits of both programs will require about 7.1 percent of general income tax revenues in 2010. [See Figure I.] As the baby boomers begin to retire, that number will soar, primarily because of the expansion of Medicare. As a result, it will be increasingly difficult for the federal government to continue spending on other activities:

- In the absence of a tax increase or benefit cuts, by 2012 the federal government will require one out of every 10 dollars of general income tax revenues to keep its promises to seniors and balance its budget.

- That means, roughly speaking, the federal government will have to stop doing one in every 10 other things it has been doing by 2012.

- By 2020, the federal government will have to stop doing one in every four things it has been doing.

- By 2030, about the midpoint of the baby boomer retirement years, the federal government will have to stop doing almost one in every two things it does today.

- Education, national defense, housing, energy, Social Security — all of these activities of government will have to be put aside, if health care promises to the elderly are to be met.

Along the way, Medicaid spending threatens to crowd out every other activity of state and local governments, and private health care spending threatens to crowd out every other form of consumption.

Bad as these projections are, the reality could be even worse. According to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), if Medicare and Medicaid spending continue to grow at their historical growth rates relative to national income, health care spending will consume nearly the entire federal budget by midcentury.2

What About the Trust Funds? Like other government trust funds (highway, unemployment insurance and so forth), the Social Security and Medicare Trust Funds exist purely for accounting purposes: to keep track of surpluses and deficits in the inflow and outflow of funds. The accumulated Social Security surplus actually consists of paper certificates (non-negotiable bonds) kept in a filing cabinet in a government office in West Virginia. (Medicare saves paper by keeping all of its records electronically.) These bonds cannot be sold on Wall Street or to foreign investors. They can only be returned to the Treasury. In essence, they are IOUs the government writes to itself.

Every payroll tax check signed by employers is written to the U.S. Treasury. Every Social Security benefit check and every Medicare reimbursement check comes from the U.S. Treasury. The trust funds neither receive money nor disburse it. Moreover, every asset of the trust funds is a liability of the Treasury. Summing over all three agencies (both trust funds and the Treasury), the balance is zero. For the Treasury to write a check, the government must first tax or borrow.

The Need for Change. If policymakers wait to address these problems until they are out of control, the solutions will be drastic and painful. It is prudent to act now. What can be done?

[page]How can we control the rising cost of Medicare? Fortunately there are an enormous number of people who have answers. These include 650,000 participating doctors and 30,000 participating facilities and approximately 44 million beneficiaries. In fact, almost everyone participating in the system can produce examples of waste and inefficiency that need to be eliminated. Unlike a normal market, however, none of these people can do much about the needed improvements they perceive. And perversely, people who try to improve the system are often penalized for doing so.

Since Medicare benefits are use-it-or-lose-it, patients can economize only by forgoing care. Since doctors are typically paid fixed fees for predetermined tasks, they can economize only by reducing services and therefore reducing their income. These incentives need to change. We need to unleash the providers and encourage them to use their intelligence, their creativity and their innovative ability to make the changes needed to produce low-cost, high-quality health care. We need to unleash patients and encourage them to apply prudent shopping skills that are normal in every other market to the market for medical care.

Let’s begin with some demand-side changes. Under the current structure, seniors pay as many as three premiums to three plans (Medicare Part B premium, Medigap premium and Part D premium) and often still do not have the coverage nonseniors typically have. We propose to replace this structure with a new, simplified structure — meant to mimic the health insurance benefits the rest of Americans enjoy.3

Standard Comprehensive Plan (SCP). This is the paradigm from which all other options are points of departure. The plan has an across-the-board $2,500 deductible and comprehensive coverage above the deductible. There is only one premium needed to enroll in this plan, and it equals about 15 percent of Medicare’s total cost. All current Medicare beneficiaries will have the opportunity to enroll in a SCP as an alternative to traditional Medicare. For all future Medicare enrollees, the SCP will be the only government plan offered.

Roth-Type Health Savings Accounts. All seniors enrolled in a SCP may deposit up to $2,500 in a Roth-type Health Savings Account (HSA). These deposits are after-tax; they grow tax free; and they may be withdrawn for any purpose tax free. It is expected that most seniors who enroll in SCPs will be able to fund their HSA deposits with money that would otherwise be spent out of pocket, plus the savings on premium expenses. Those who elect some of the options described below may be able to have larger accounts — funded by third-party insurer contributions or out-of-pocket contributions. In all cases, seniors will use their HSAs to pay for expenses not paid by third-party insurance.

Private Administration. We envision that Medicare insurance will be administered by private insurers. Under the current system, Medicare is generally administered by Blue Cross — acting as a no-risk claims administrator. Under the new system, the government’s SCP plan will also be administered by Blue Cross. However, other private carriers may also offer plans, much as they do under the current Medicare Advantage Program (Part C). The government will pay these plans a risk-adjusted premium and they will be at risk, with incentives to eliminate waste and inefficiency.

Risk-Adjusted Premiums. People who are already enrolled in Medicare will continue to pay the 15 percent premium to maintain their enrollment in SCPs in future years. For those who enroll in private plans, the government will add to this amount, producing an overall premium, adjusted for health risks the senior poses. The government’s goal is to ensure that the total premium will always be sufficient to purchase the SCP package of benefits, although for private plans this premium will be determined by competition in the marketplace. (The current method of making risk-rated premium payments can serve as a guide; however, there are too many constraints imposed by special interest pressures.)4 For people yet to retire, there will be additional costs to the retiree as described below.

Other Insurance Options. Seniors will have other insurance options. Following the method described above, we will be able to fix the government’s liability. Once the government (taxpayer) contribution has been set, insurers will be able to offer different benefit packages, with higher or lower overall premiums. These options would include HMOs, PPOs, HSA plans with higher deductibles and Special Needs Plans with HSAs. Also, retirees could remain in their previous employer’s plan (if the employer is willing) by directing the government’s contribution to that plan.5

Seniors who choose one of the options may have other HSA opportunities. For example, a senior choosing a $5,000 deductible will be able to make a $5,000 annual HSA deposit, with the extra $2,500, say, covered by a $1,250 deposit by the insurer and $1,250 from the enrollee.6

New Health Savings Account Design. Private insurers offering HSA plans will not be required to have an across-the-board deductible. They will instead be allowed to reduce the deductible to zero for services they want to encourage (such as medications for schizophrenia) and maintain high deductibles for services for which patient discretion is appropriate and desirable (for example, choice of drugs for arthritis or allergies). Additionally, plans will be able to carve out whole categories of care (such as primary care or diagnostic tests), which patients will pay entirely from their HSAs without any deductible or copayment.7

Insurers will also be able to create special HSA accounts for the chronically ill, allowing them to manage more of their own health care dollars. The “Cash and Counsel” experiments — pilot projects in more than half the states — have provided one possible model to follow. In these programs, disabled Medicaid patients manage their own health care budgets and can hire and fire those who provide them with custodial and even medical services. Incredibly, the satisfaction rate in these programs is 90 percent.8 The insurer’s incentives to improve plan design will be enhanced by long-term contracts (discussed below).

Expected Changes in Behavior. Almost three decades ago, a RAND study found that when people pay a substantial amount of their health care bills out-of-pocket, they reduce their health care spending significantly, with no apparent harmful effects on their health.9 Since that time, there have been a number of experiments — both within this country and abroad — exploring ways to create greater patient cost sharing without encouraging people to forgo needed care. These include Medisave Accounts in Singapore (dating from 1984),10 Medical Savings Accounts in South Africa (dating from 1993);11 and in the United States, a Medical Savings Account pilot program (dating from 1996),12 the current Health Savings Account program (dating from 2004),13 Health Reimbursement Arrangements (dating from 2002) and even cash accounts in Medicaid.14 Many of these experiments have been subjected to considerable academic scrutiny.

The consensus seems to be that when patients are managing their own health care funds, they make prudent decisions — say, substituting generic drugs for brand name drugs, reducing unnecessary trips to physicians’ offices and hospital emergency rooms, engaging in comparison shopping, seeking second opinions on surgery, questioning the necessity of certain diagnostic tests and so forth.15

Unfortunately, most of these patient decisions are being made in the context of a market in which there is little price or quality transparency and in which there are limited support tools to help patients make wise choices. Undoubtedly, the market would work much better if providers were free to repackage and reprice their services in a way that encouraged them to compete for patients based on both price and quality of care. To that end, let us now consider some supply-side changes.

[page]Doctors participating in Medicare today must practice medicine under an outmoded, wasteful payment system. Typically, they receive no financial reward for talking to patients by telephone, communicating by e-mail, teaching patients how to manage their own care or helping them be better consumers in the market for drugs. Medicare pays by task, and these are not reimbursable activities. So doctors who help patients in these ways are taking away from billable uses of their time.17

In fact, physicians who help patients in these ways may end up with less payment from Medicare. To make matters worse, as Medicare suppresses reimbursement fees, doctors are increasingly unable to perform any task that is inadequately reimbursed. Other health care providers face the same perverse incentives. All too often, high-cost, low-quality care is reimbursed at a higher rate than the alternative, and Medicare’s payment rules get in the way of providers working together to improve health care.18

How can we produce high-quality care for a cost that is well below the price we are paying today? Fortunately, we do not have to speculate. There are hundreds of examples of efficient, high-quality care, and many of them have been studied and described in the academic literature. For example, studies by researchers at the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice imply that if everyone in America went to the Mayo Clinic for health care, the nation could reduce its annual health care bill by one-fourth.19 If everyone went to Intermountain Healthcare in Salt Lake City, the nation could reduce its health care spending by one-third.20 Studies by Dartmouth21 and the National Center for Policy Analysis22 imply that if every region of the country practiced medicine the way the most “efficient” or low cost regions do, we could cut Medicare spending by one-third to one-fourth of its current level.

How do we get from here to there? Here are two practical examples of what would be involved.

Case Study: Geisinger Health System in Central Pennsylvania.23 Geisinger provides a useful example. It offers a 90-day warranty on heart surgery, similar to the type of warranties found in consumer product markets. If the patient returns with complications during that period, Geisinger promises to provide treatment without sending the patient or the insurer another bill.

Unfortunately, Geisinger incurs financial losses under this practice, even as it saves money for Medicare overall. This is because health care organizations like Geisinger are paid more when patients have complications that lead to more visits, more tests and more re-admissions. (Most hospitals make money on their mistakes!) What is needed is a willingness to pay for such guarantees. Medicare should be willing to pay more for the initial surgery if taxpayers save money overall.

Case Study: Virginia Mason Medical Center in Seattle.24 In another innovative example, Virginia Mason offers a new approach to the treatment of back pain, a source of considerable medical spending nationwide. Under the old system, a patient would often first receive an MRI scan or specialty consultation and other tests before referral to a physical therapist. Under the new system — which cuts the cost of treatment in half — patients are first seen by a physical therapist unless additional diagnostic measures are clearly indicated, and receive an MRI scan only if the therapy doesn’t work and symptoms persist.

The new system improves efficiency and saves money for payers but leaves the providers financially worse off. As in the case of Geisinger, Medicare should permit a new payment arrangement — one that is win-win for Medicare and Virginia Mason.

New Payment Opportunities. Medicare providers should be reimbursed more efficiently. We should be willing to reward doctors who raise quality and lower costs — who improve patient access to care, improve communication and teach patients how to be better managers of their own care. Providers do not need pay-for-performance; rather, performance for pay — with ideas and proposals coming from the supply side of the market (which is more knowledgeable about potential improvements than the demand side).

Any provider should be able to propose and obtain a different reimbursement arrangement, provided that (1) the total cost to government does not increase, (2) patient quality of care does not decrease and (3) the provider proposes a method of measuring and assuring that (1) and (2) have been satisfied.

Evaluating Proposals. In evaluating proposals, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) needs to depart from current procedures in four important ways. First, providers should not be “at risk” for the system-wide costs they propose to lower. For example, better diabetic care initiated by pharmacists in Asheville, N.C., apparently reduced physician visits and episodes of emergency room care.25 Yet the costs the pharmacists reduced are costs they do not control. Services provided by walk-in clinics in shopping malls may also lower physician and emergency room visits. But these costs are also not under the control of the clinic.

Second, approvals should be granted based on reasonable expectations that costs will be lowered and quality increased. For example, there are dozens of case studies documenting higher-than-average quality and lower-than-average cost. A provider who makes a prima facie case that he intends to replicate the standard operating procedures used in these case studies should be presumed to be successful.

Third, the CMS should view these arrangements as venture capital investments —understanding at the outset that many ventures will not be successful.

Finally, the goal of these arrangements is not to save as much money as possible for the CMS. The goal is to encourage a competitive market on the provider side — in which every doctor and every facility is encouraged to continuously search for ways to rebundle and reprice medical services in quality-enhancing, cost-reducing ways.

Once one hospital or doctor group implements an arrangement with better payment for better results, there will be competitive pressures on other providers to find new and innovative ways of raising quality and lowering costs. Plus, once Medicare takes these steps, private insurers can adopt similar payment systems more easily. Medicare and the private sector will be pushing in the same direction, for better care — not just more services.

Rescinding Contracts. After some reasonable period of time (agreed to in advance) the CMS must make a reasonable determination about the success of the agreement. If there is clear evidence of failure, the contract should be ended. If the new system shows clear evidence of success, the contract should be extended. If the evidence is mixed, the provider might be put on notice that the contractual arrangement is in jeopardy.

Streamlined Approvals. For the reform to be workable, the transactions must be easy to negotiate and consummate. Paperwork and time delays are the enemy of entrepreneurship. However, given a willing Medicare administration, the process of reform should not take long. There are already low-cost, high-quality pockets of excellence just waiting to be replicated.

Relaxation of the Stark Restrictions. Another essential ingredient is allowing doctors and facilities to work together as a team — making needed improvements and profiting from those improvements. To facilitate this change, we must repeal or relax regulations that prohibit profitable provider arrangements, including the so-called Stark laws.

[page]The purpose of HIRA accounts is to allow people to prefund some of their post-retirement health care benefits, so that they do not have to rely as heavily as currently projected on future taxpayers. Eventually each generation will pay its own way. By saving enough during their working years and paying additional amounts from their retirement income, they will be able to completely cover the cost of care during the years of retirement.

Contribution Levels. We envision an initial mandatory contribution level of 4 percent of payroll — 2 percent each from the employer and employee. These amounts may rise in future years if they prove inadequate to achieve sufficient pre-funding.

Investment of HIRA Funds. Unlike some proposals for Social Security reform, we propose that all HIRA funds be invested in diversified, conservative, international portfolios, consisting of stocks, bonds, real estate and other assets. Some argue that private account funds should be invested in risk-free government bonds. That is an acceptable approach for a small program with a modest amount of money to invest. However, for the size of the forced saving considered here, there are not enough bonds to be purchased. Nor should the federal government borrow enough to meet the demand. That would be irresponsible. As a practical matter, there is no alternative to investing in the nation’s capital stock.27

Management. The investment of HIRA funds will be managed by private security agencies. As is the case in Chile’s social security system, these companies will compete not so much on portfolio selection (about which they will have little choice) but on reporting, accounting and other services.

Contingent Ownership. Individuals are the nominal owners of their HIRAs, but their rights to these funds are contingent on several factors. First, they must survive to the age of eligibility for Medicare. In case of an early death, a worker’s HIRA funds are distributed to the accounts of all remaining workers. In this sense, an individual’s property rights in a HIRA are like contractual rights under an annuity insurance contract. Second, the SCPs will receive risk-rated premiums for all their enrollees. In the early years, the risk rating can be entirely accomplished by adjusting the government’s contribution. Several simulation models are described in a later section. The Core and Intermediate Models would allow for the HIRA balances in the large or “overfunded” accounts to be taxed to make risk-rated premium payments on behalf of individuals with “underfunded” accounts. At this point, HIRA owners are entitled to a “risk-rated annual withdrawal,” in a manner described more fully below.

Relation to Disability. Although not a formal part of this proposal, a natural extension of these ideas is to consider integrating Medicare post-retirement reform with reform of Social Security disability insurance and Medicare for the disabled. Chile has shown that the costs for disability can be cut in half with private accounts and better economic incentives.28

[page]HIRA Options. Owners of HIRA accounts will be given these options: (1) they can cede their HIRA funds to the government and enroll in a conventional Medicare SCP plan, (2) they can purchase an annuity — a stream of cash for their remaining years to be used to pay private health insurance premiums and to purchase health care directly, or (3) they can keep the account and withdraw an amount each year for the payment of premiums — with the withdrawal percentage determined by the government.29

Timing of HIRA Options. Workers will be able to make an election at any time within 10 years of the age of eligibility for Medicare.30

Using HIRA Funds to Purchase Private Health Insurance. As with current Medicare enrollees, the point of departure for future beneficiaries will be enrollment in a SCP plan. Individuals will pay a risk-adjusted premium made up of three parts: (1) their 15 percent Medicare premium (2) the annual annuity or programmed HIRA withdrawal amount and (3) a contribution from the government. The government’s contribution is calibrated so that the risk-adjusted premium is sufficient to pay the enrollment premium.

The base insurance plan is one with a $2,500 deductible that is indexed to Medicare per capita cost growth. Once the government’s contribution is calculated in this way, seniors may use those same dollars to enroll in the other plan options described above.

Long-Term Insurance Contracts. Unlike the current Medicare advantage program, this program will be based on a long-term relationship between seniors and their insurers rather than a system that encourages annual plan switching. A long-term relationship with an insurer typically also makes possible a long-term relationship with providers of care. In addition, if insurers know they will be responsible for care in the future, they will have incentives to make investments today that have future health consequences. Hence, the insurance contract should be at least five years in duration, and perhaps even longer.

Opportunities to Switch Plans. Even though most seniors will have long-term relationships with their insurers, that does not preclude the opportunity to switch plans. Certainly, seniors should be able to make another choice if their plan is abusive or fails to honor its contracts.

More generally, we want to encourage health plans to specialize if there are advantages to doing so. For example, one plan might become the best at cancer care and try to solicit cancer patients from other plans. In order to make such a switch, all three parties (patient, original insurer, new insurer) must agree; and achieving agreement may involve severance payments between the insurers. In this way, the new system will encourage a “market for sick people” in which health plans will find it in their financial self-interest to attract patients by providing efficient, high-quality care.31

End of Life Care. Under the current system, the only way terminally ill patients can get benefits from Medicare is by spending more on health care. This may be one reason why one-third of all Medicare spending is on patients in the last year of life.32 These incentives need to be changed. A patient who forgoes expensive treatment and enrolls in a hospice or who simply goes home is saving the system money. Clearly it is in the taxpayers’ interest to financially reward people who reduce taxpayer obligations. At a minimum, terminally ill patients who forgo care should get to keep some or all of their remaining HIRA funds rather than continue to pay premiums.

Encouraging Efficient Choices. Patients can also reduce overall spending by making other decisions. In the international marketplace, hospitals are competing for patients based on price and quality. Many of these facilities have affiliations with centers of excellence in the United States, including, for example, the Mayo Clinic. In general, surgery in Europe costs one half of the typical U.S. charge and procedures in India and Thailand costs as little as one-third, one-fourth or one-fifth of the expected U.S. charge.33 In the current system, Medicare doesn’t pay for care outside the United States. But why not? Patients in private plans should be able to get a rebate of some or all, of their HIRA balances if they save even more money for their insurer (and, therefore, for Medicare).

Encouraging More Efficient Insurance. Closely related to the idea of spending less on care is the idea of choosing less expensive insurance. What if a senior chooses a plan with a $10,000 deductible? What if the plan does not cover “heroic medicine”? What if it excludes organ transplants and implantable devices? Surely people who make these elections and avoid costs should financially benefit from them. Presumably, there is some minimum insurance we want everyone to have. For choosing insurance that covers the minimum, but avoids many expensive options, people should get rebates of some or all of their HIRA balances.

Under Social Security, contributions (taxes) are a percent of wages and so are retirement benefits. In a sense, the structure of Social Security mimics the structure of a private pension plan in which workers mainly fund their own benefits with their own contributions. This is why a pay-as-you-go system can be replaced with a funded pension system (as it has, say, in Chile) without changing its fundamental appearance. Medicare is different. There is virtually no relationship between contributions and benefits in this program — either over time or within an age group.

The Current Financing System. Under the current arrangement, workers pay a 2.9 percent payroll tax — which means that contributions are proportional to income. At the time of eligibility for enrollment, however, all seniors essentially get the same package of benefits over a lifetime. High-income beneficiaries, therefore, pay more payroll taxes — substantially more — than low-income beneficiaries for the same insurance plan. In addition, general revenues (primarily from corporate and individual income taxes) support 75 percent of Medicare Parts B and D. These taxes tend to be paid by higher income workers and owners of capital.

Reformed Financing System: Medicare SCP Plans. Under the new, partially funded Medicare system, we retain the practice of making contributions proportional to income. For those who elect to cede their HIRA funds to the government and enroll in a SCP at age 65, the price of enrollment will vary with income — since higher income workers will accumulate larger HIRA accounts. As under the current system, people the same age will incur vastly different costs for the same benefit package.

Reformed Financing System: Private SCP Plan. For those who enroll in private SCPs, the government’s role is to top up their 15 percent premium plus their annual HIRA amount (annuity payment or withdrawal) to reach a total risk-adjusted premium needed to buy the SCP package of benefits. This means the government will contribute more to the health insurance of low-income seniors (who have smaller HIRA amounts) than it will for high-income seniors. It will also contribute more to insurance for the sick (who will require larger risk-adjusted insurance premiums) than for the healthy. In this sense, the role of the government is to redistribute from high-income to low-income and from the healthy to the sick within each age cohort.

Long-Term Financing Arrangement. Ultimately, we would like a system in which the average worker accumulates sufficient funds over his worklife to completely finance his own post-retirement health insurance (in addition to the 15 percent annual premium payment made from retirement income). But if we achieve this goal for the average worker, we will have saved too much or too little for every worker who is nonaverage. The government will have to supplement the premium payments of seniors who are relatively poorer and/or sicker. In order to do this, it will need to take from the HIRA payments of the relatively richer and/or healthier. This will involve a “tax” (or negative subsidy) on the HIRA accounts of wealthier and healthier seniors.

Changes in Tax Rates Through Time. In general, we want each age cohort to make contributions over their worklife sufficient to fund their SCPs during the years of retirement (in addition to the 15 percent annual premium payment made from retirement income). Since it is impossible to accurately predict the cost of health care 40 years into the future, there is no particular reason to believe that the initial mandatory contribution rate will need to be kept constant. Every five or 10 years we expect adjustments to be made, as new information about the future becomes available.

How does the plan outlined above differ from what might arise in a free market agreement among voluntary, consenting individuals?

Purely Private, Contractual Relationships. Imagine a large number of 20-year-olds, contemplating their future. They would like to make sure they will have access to health care during the years of their retirement. But how can they secure this objective? Ideally, each would save a certain percent of his income over the course of his worklife and use the accumulated savings to purchase health care and health insurance during the retirement years.

The problem: No individual can reasonably predict what his life cycle income will look like, what his health status (and therefore health costs) will be at age 65 or how long he will even be alive. Fortunately, predicting for the group as a whole (or what is almost the same thing: predicting what will happen to the average person) is much easier than predicting for a single individual. And even though no one can reliably predict what will happen to the average person over 45 years, we can always begin with an estimate and readjust every 5 or 10 years (raising or lowering the needed contribution rate) as experience dictates.

This is where insurance comes in. An individual acting alone faces the risk that his own experience will deviate from the average — possibly doing much better, possibly doing much worse. The downside risk is that the individual will reach the retirement years with too little to pay for his needed health costs. It is precisely this risk that people, in principle, could insure against. Ideally, a voluntary insurance contract would insure the individual against (a) unexpected changes in income, (b) unexpected changes in health status and (c) nonaverage mortality. There is no reason in principle why this relationship could not be voluntary, consensual and completely private.

It may also be possible to protect individuals against the risk of market volatility. For example, the day an individual reaches age 65, the market may be high or it may be low. However, a smoothing of returns over cohorts spanning, say, 5 to 10 years may provide insulation against wide swings in investment returns.34

A Mandatory System. Like the current Medicare program, the reformed system we propose would be mandatory. However, it would be much closer to a completely private system than what we have today.

Why does participation have to be mandatory? It doesn’t. And it shouldn’t if we are willing to allow people to live with the consequences of their own decisions and their own bad luck. However, there is no evidence of any such willingness. As a practical matter, society is going to provide substantial health care to people in their twilight years, even if they have negligently and willfully saved not a penny for their own post-retirement health care needs. Thus without mandated savings, individuals could game the system — consuming all of their income during the preretirement years and relying on the charity of others during retirement.

In this sense, the argument for forced savings for post-retirement health care is similar to the argument for forced savings for (Social Security) retirement income. It basically ensures that individuals pay their own way and precludes opportunities to exploit the generosity of other members of their cohort.

Harder to defend is the practice of charging everyone the same percent of income (same payroll tax) to enter the pool. Surely, a private insurer would not treat all 20-year-olds the same, even though the payout is 45 years down the road. Although we discussed above the higher burden on higher-income enrollees, the current structure of Medicare is far less redistributive than one might suppose. Although low-income people pay fewer dollars into the system over their worklives, they die earlier, and after age 65 they consume less health care than higher income retirees.35

A Reformed Medicare System. There are two primary sources of funds to pay for health care in a reformed Medicare system: accumulations in HIRA accounts and money that flows through government. We envision that HIRA funds will be managed by private sector trusts, that the relationship of the trusts to the beneficiaries will be contractual and that an individual’s property rights in these funds will enjoy the full protection of due process of law. Although these trusts will be subject to government-imposed rules requiring safe and prudent management, the government will not be able to seize the funds any more than it can seize the funds in someone’s IRA.

As noted, during the accumulation phase of an individual’s life, his right to his HIRA contributions is contingent on survival to age 65. For those who do not survive, the HIRA balance remains in the private sector and is redistributed to the remaining members of the insurance pool. During the decumulation (retirement) phase, individuals have contingent rights to their annual annuity payments or programmed withdrawals.

As long as government funds are used to complete the process of risk adjustment, individuals may be said to have a direct property right in their HIRA annuities. However, as HIRA balances grow relative to taxpayer commitments, HIRA annuities themselves will be subject to an insurance arrangement. Specifically, individuals will have a property right to a risk-adjusted annual payment, based on the worklife contributions they and their cohorts make. This annual payment will be adjusted for four types of risk: (1) income volatility, (2) changes in health status, (3) mortality and (4) market volatility.36

Some may question whether the property right to a risk-adjusted annual payment is as valuable or desirable as the right to the exact dollars an individual contributes over a worklife. In fact, the former is more valuable than the latter. The reason: the former provides insurance protection that is worth more than it costs.

In contrast to the contingent-insurance property right individuals will have with their HIRA funds, they will have no legally enforceable right to the funds that come from government. Although under our proposal the government’s objective is to ensure that every retiree has access to an affordable SCP plan, this is not a contractual commitment any more than the current Medicare system makes contractual commitments to provide future health care to beneficiaries. As federal court rulings have affirmed for Social Security, a current Congress cannot bind future Congresses. As the need for change arises, we expect that government can and will change its policies.

It may seem that risk-adjusted payments on behalf of retirees discriminate against people who adopt healthier lifestyles and thereby encourage unhealthy behavior. While this may be true of spending in any given year, a new study finds that over a lifetime, people who adopt healthy lifestyles actually spend more health care dollars than obese people and those who smoke.37 As a result, people with healthy behaviors may gain from a system of risk-adjusted payments during their senior years. Healthier retirees also gain by being more likely to be able to use their unspent HSA balances for nonhealth purposes.

[page]A major trend in post-retirement living is the assisted living facility. These entities typically offer room and board — in some cases quite luxurious — plus nonacute health care. In theory, an initially healthy senior could progress through Alzheimer’s disease and then death without ever leaving the facility.

The emergence and growth of assisted living facilities causes us to focus on an often ignored reality: It is becoming increasingly difficult to separate living needs from health care needs — especially for senior citizens. That being the case, why do we need three separate programs: Social Security for living expenses, Medicare for health care and Medicaid as a fall back insurance for long-term care? Why can’t all three programs be rolled into one? They could.

In a reformed Social Security system, each generation would save through private accounts for its own retirement living expenses. In a reformed Medicare system, each generation would save through private accounts for its own post-retirement health care. But why have two accounts? Why have separate investment strategies? Wouldn’t a single account be more efficient and make more sense? We believe it would. Additionally, there is no reason why the same account could not also be used for long-term care insurance — thereby replacing the largest, fastest growing part of Medicaid.

It might work like this: At the time of retirement, an annuity would be purchased which generates two separate cash flow streams. One would be for living expenses (like a pension) and the other would be for health insurance (like the HIRA accounts described above). However, the two income streams could be combined and redivided in different ways. For example, one stream of payments could cover the cost of living, outpatient care and long-term care at an assisted living facility, while the remaining stream pays for insurance for catastrophic inpatient care.

The approach to Medicare reform outlined here is based on the idea that each generation should pay its own way. However, even after mandatory saving over an entire worklife, there will be those who have not saved enough to fund their own post-retirement health insurance. Should the financial shortfall experienced by people be made up by the members of their age cohort? Or should this deficit be viewed as more properly a concern of society as a whole? If the latter, then we may want to keep a residual part of the program to be funded by taxpayers —say, through an assessment roughly the size of the current payroll tax.

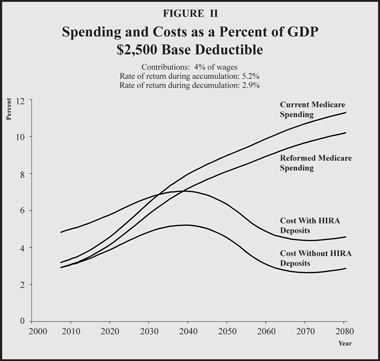

[page]Although we have considered a large number of reforms in the preceding section, here we attempt to simulate the effects of just a few of those reforms. We begin with the core model, described above. We also consider two other reform proposals.

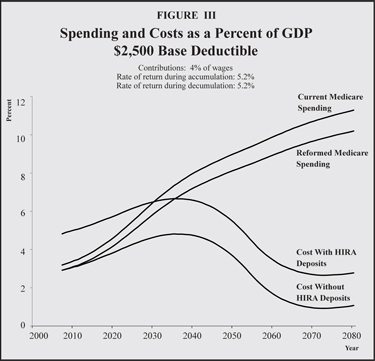

Simulation Assumptions: The Core Model. In order to simulate the effects of our proposed reform, we make the following assumptions [see Figures II and III]:

- Future health costs will grow at the same rates assumed by the Medicare Trustees. Note: This is a conservative assumption, since it ignores the effects of increased incentives we propose to control costs.

- All current Medicare enrollees opt to enroll in SCP plans. This assumption is made for ease of computation and has a very minor impact.

- All future participants enroll in SCP plans at age 65.

- The mandatory contribution is 4 percent.

- All HIRA funds are invested in a balanced portfolio of assets earning 5.2 percent during the accumulation phase and 2.9 percent (for the annuities) or 5.2 percent (for programmed withdrawals) during the decumulation phase. This capital market return is lower than what others have suggested.38

- The base SCP plan begins in 2007 with a $2,500 deductible and is indexed to Medicare per capita cost growth.

- The demand-side and supply-side effects of higher deductibles are modeled based on the results of the RAND Health Insurance Experiment and other studies.39

- The government makes an annual contribution which, when combined with a 15 percent premium payment and an individual’s HIRA annuity or programmed withdrawal, is sufficient to pay the risk-rated premium needed to purchase an SCP plan for every retiree.

- If the HIRA balances of some individuals become so large that no government contribution is needed to purchase an SCP plan, the government taxes the surplus funds of some individuals in order to make risk-adjusted payments for others.

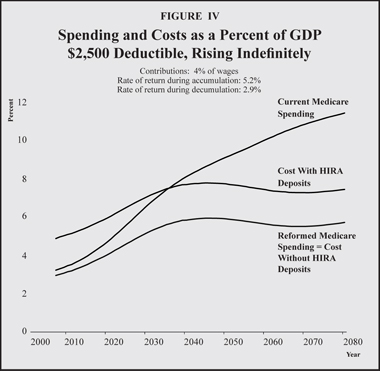

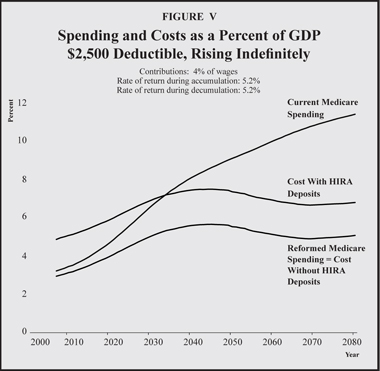

An Alternative Way to Purchase Private Health Insurance: The Rettenmaier-Saving Plan. Andrew Rettenmaier and Thomas Saving have a proposal that we model below.40 [See Figures IV and V.] Specifically, the retiree’s entire HIRA annuity is deposited in the Roth-type HSA and the retiree’s across-the-board deductible increases dollar for dollar with the HIRA annuity amount. For example, if the HIRA annuity is $1,000, the total deductible would rise from $2,500 to $3,500.

The advantage of this approach is that it generates more demand-side incentive effects for every retiree and, as a consequence, it generates more supply-side effects as well. Therefore, overall health care spending will be lower than otherwise and the retirees will be able to devote any of their annuities that are not spent on health care to the consumption of other goods and services. Another advantage is that workers will not view their contributions as a pure tax — as they would with the core reform that requires the entirety of their annuities be devoted solely to health care consumption. The downside of this approach is that it leaves taxpayers with a higher long-run burden than the core model. However, retirees are able to consume more of other goods and services from the residual amounts of their HIRA annuities that are not spent on health care. This higher consumption is not reflected in the following simulation results.

The assumptions for the Rettenmaier-Saving Model are the same as for the Core Model except that:

1. HIRA annuities (or programmed withdrawals) are deposited directly into the recipient’s HSA and the across-the-board deductible rises dollar for dollar with each contribution. The annuity combined with the indexed-based deductible defines the upfront cost sharing for each retiree.

2. Individuals have a property right in their entire HIRA annuity, regardless of income or health status.

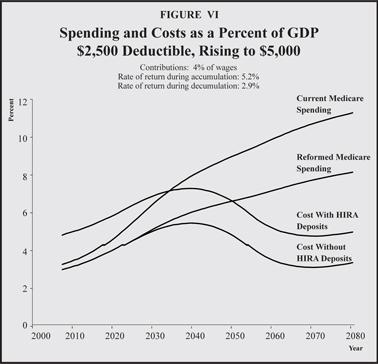

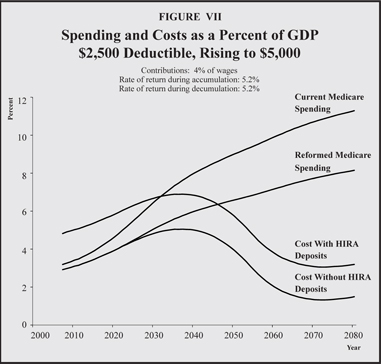

Another Way to Purchase Private Health Insurance: The Intermediate Model. Under the Rettenmaier-Saving proposal, accumulations in HIRA accounts can become quite large over time, especially for high-income workers. In some cases the annual annuity payment could even exceed per capita Medicare spending. The incentive effects of a high deductible, however, are largely captured by the time it reaches $5,000. For this reason we consider an intermediate model in which the maximum deductible is $5,000. [See Figures VI and VII.] This amount is indexed by per capita Medicare spending. Retirees face cost sharing up to the maximum deductible and retain any unspent HIRA annuity deposits. If an individual’s annuity amount is greater than the difference between the $5,000 maximum deductible and the base deductible, the excess is used to pay for general Medicare spending on all beneficiaries.

The assumptions under the Intermediate Model are the same as for the Core Model except that:

- HIRA annuities (or programmed withdrawals) are deposited directly into the recipient’s HSA and the across-the-board deductible rises dollar for dollar with each contribution up to a maximum deposit of $2,500 and a maximum deductible of $5,000 (with amounts indexed to per capita Medicare expenditure growth).

- Individuals have a property right in their entire HIRA annuity up to the indexed value of the maximum deductible, regardless of income or health status.

Simulation Results. Figures II through VII show the simulation results for the three models and the two rate-of-return assumptions during the decumulation phase. Note that in each of the graphs:

- The upper line represents Medicare spending (funded by taxes plus premiums) under the current system.

- The next line down represents Medicare spending under the reformed system (funded by taxes plus premiums plus prefunding through HIRA accounts).

- The next line represents the contemporaneous cost of the reformed program (measured as the sum of taxes plus premiums needed to pay benefits in each year) plus contributions to HIRA accounts needed to continue the process of prefunding future health care expenses.

- The bottom line represents only the contemporaneous cost (taxes plus premiums) and is the one most comparable to the top line.

As all six figures show, the effects of prefunding combined with better incentives have a dramatic impact on the future financial health of Medicare. Eventually, the taxes and premiums needed to pay benefits comparable to what Medicare promises today will be only a fraction of what they will need to be in the absence of reform. Specifically:

- Under the current system, the taxes and premiums needed to support Medicare spending will more than triple, growing from 3.2 percent of GDP today to 11.3 percent by 2080.

- By contrast, under the Core Model with a 2.9 percent decumulation rate of return, the taxes and premiums need to support Medicare spending will be 2.9 percent of GDP by 2080.

- Under the higher (5.2 percent) decumulation rate of return, the burden of Medicare will return to its current level soon after midcentury and it will be only one-third of the current level by 2080.

The burden of Medicare spending achieves comparable results under the Intermediate Model.

Although both models bring the burden of Medicare spending back to current levels, by the time today’s teenagers reach the age of retirement the Intermediate Model has a bigger impact on health care spending, bringing the total down to 8.2 percent of GDP as opposed to 10.2 percent with the Core Model. Relative to the Core Model, the Intermediate Model cuts spending by one-fifth. Figures IX and X show how the burden for taxpayers will change over the next 73 years: Whereas taxes pay for almost nine of every 10 dollars of Medicare spending today, under the Intermediate Model taxes will be needed for only one in every four dollars of spending in 2080.

As explained in the Appendix, we assume that the Core Model has demand-side effects only. For the Intermediate Model, however, we estimate supply-side effects as well:

- By 2080, with a 2.9 percent return during the decumulation phase, the Intermediate Model will reduce the burden of Medicare by 10.2 percentage points of GDP, relative to what otherwise would have happened.

- Of the total reduction, about 70 percent (7.1 percentage points) is produced by the effects of prefunding, about 20 percent (2.1 percentage points) is produced by demand-side effects, and about 10 percent (1.0 percentage points) is produced by supply-side effects. [See Figure VIII.]

Consider now the Rettenmaier-Saving reform plan (illustrated in Figures IV and V), which allows rising HIRA contributions through time to be contributed to the retirees’ HSA accounts along with dollar-for-dollar increases in the across-the-board deductible. The results for the 5.2 percent/2.9 percent return assumptions are as follows:

- This reform substantially reduces Medicare spending — falling from 11.3 percent of GDP in 2080 to 5.7 percent — virtually cutting total spending in half.

- The remaining burden of taxes and premiums, however, is 70 percent larger than under the Intermediate reform (5.7 percent versus 3.3 percent, with a 2.9 percent decumulation rate).

- The total cost of the reform is 7.4 percent of GDP in 2080 including workers’ contributions to their HIRA. This compares to 5.0 percent of GDP under the Intermediate reform.

The reason for this apparent anomaly is that HSA account-holders are choosing to spend substantially more of their HSA funds on other goods and services (rather than health care) than is allowed under the Intermediate plan.

Conclusion. Health care spending has been growing at roughly twice the rate of growth of national income for about four decades. If that trend continues, health care will eventually crowd out every other form of consumption — there will be nothing left for food, clothing, housing and so forth. Clearly, we are on an impossible path.

The simulations in this study are based on the assumptions of the Social Security/Medicare Trustees. These assumptions presume health care spending will moderate, eventually growing no faster than the average wage. But the Trustees do not tell us what changes will occur to bring about such moderation.

Given the Trustees’ assumptions, we have proposed a set of reforms that will solve the long-term financial problems of Medicare. These include: (1) allowing providers to repackage and reprice their services in ways that improve quality and reduce price, (2) allowing beneficiaries to manage more of their own Medicare dollars through cash accounts called Roth Health Savings Accounts, and (3) requiring the working age population (along with their employers) to prefund much of their post-retirement health care benefits by saving 4 percent of wages from now until the time of retirement.

These reforms are expected to moderate the growth of Medicare spending and to shift the burden of spending from taxpayers to workers beneficiaries over time. As a result, the taxpayer burden for Medicare as a percent of national income should be no higher by midcentury than it is today. Of the future reduction in taxes and premiums, 10 percent will be due to supply-side reforms, 20 percent will be due to demand-side reforms and 70 percent will be due to the effects of prefunding.

Furthermore, all of these changes are accomplished while preserving the progressivity of the current system.

by Andrew J. Rettenmaier

The demand-side effects of higher deductibles on Medicare spending are derived from estimates based on the RAND Health Insurance Experiment (HIE).41 The total deductible is compared to total per-capita spending on Medicare-covered services by age.42 This ratio is compared to similar ratios from the RAND simulation results to stratify the effects of different deductible amounts. Today, a base deductible of $2,500 is equal to about 17 percent of estimated total average spending on services covered by Medicare. At the time of the RAND experiment, a deductible of $100 represented about 12 percent of average spending by individuals who had access to free care, while a deductible of $200 was equal to 25 percent. The estimate of the effect of a $2,500 on a retiree’s demand for health care would fall between the 12 and 25 percent reduction suggested by the RAND results. The reduction in health care spending due to total deductible amounts that rise relative to average spending are estimated in the same way. Such a rise will occur with the intermediate case and the Rettenmaier–Saving plan.

Estimating possible supply-side responses due to higher cost sharing is less straightforward, though recent work has hinted that the supply-side responses may be substantial. Amy Finkelstein finds that as much as 50 percent of the real per capita health care expenditure growth between 1950 and 1990 can be attributed to the reduction in out-of-pocket spending.

Previous estimates of the degree to which declining out-of-pocket spending explains expenditure growth suggested a smaller effect than those obtained by Finkelstein. Joseph Newhouse used the RAND HIE to determine the percentage of the growth in real per capita health care spending between 1950 and 1980 that is due to the change in out-of-pocket spending over that time period. He notes that the RAND HIE results indicated that moving from an average coinsurance rate of 33 percent to a zero rate at a point in time produced a 40 to 50 percent increase in demand. Given that the average realized coinsurance rate dropped from 67 to 27 percent between 1950 and 1980, or 40 percentage points, he estimates that demand should have increased about 50 percent as a result of the change in the coinsurance rate. However, there was a 400 percent increase in real spending over that time period. He therefore concludes that the increase in real spending was eight times as large as one would expect from the change in the coinsurance rate.

Finkelstein estimated that spending increased 37 percent during the first five years of the Medicare program. Medicare decreased the population average coinsurance rate by 7 percentage points. Thus, the 50 percentage point decrease in the coinsurance rate between 1950 and 1990 would increase spending by 264 percent which accounts for about half of the total real per capita spending increase over this period; this is in contrast to the one-eighth estimated by Newhouse. Finkelstein notes that Medicare provided incentives that allowed health care suppliers, particularly hospitals, to invest in capital.

A reform that potentially moves cost sharing in the opposite direction of the cost sharing percentages between 1950 and 1990 will likely produce supply-side responses in addition to the demand-side responses that will both lower the level of spending as well as the growth rate in spending. In the present study, the adjustment due to the higher deductibles is estimated in two stages. The first stage is the demand-side adjustment due to the rising total deductible as described above.43 The second stage of the adjustment attempts to account for effects of the change in the realized percentage of out-of-pocket spending. In the core case this percentage stays the same through time, so no adjustment is made to the per capita growth rate used by Medicare. In both the intermediate case and the case of the Rettenmaier-Saving plan, however, realized out-of-pocket spending as a percent of total spending would rise. The estimates in Newhouse and Finkelstein are both based on realized out-of-pocket spending as a percent of total spending, not deductibles and copays as a percent of spending. In the case of the Rettenmaier-Saving plan, the realized out-of-pocket spending as a percent of total spending would rise by an estimated 15 percentage points by 2050. The second-stage adjustment is estimated by assuming that this rise in out-of-pocket spending reduces the real growth in per capita spending by 2050 by 15 percent.

___________________________

Amy Finkelstein, “The Aggregate Effects of Health Insurance: Evidence from the Introduction of Medicare.” Quarterly Journal of Economics, February 2007.

Joseph Newhouse, “Medical Care Costs: How Much Welfare Loss?” Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 6, No. 3, summer 1992.

[page]

1. [Note: The following National Center for Policy Analysis studies are available on-line at NCPA.org.] Peter Ferrara, John C. Goodman, Gerald Musgrave and Richard Rahn, “Solving the Problem of Medicare,” Policy Report No. 109, 1983; John C. Goodman and Gerald Musgrave; “Health Care for the Elderly: The Nightmare in our Future,” Policy Report No. 130, October 1987; NCPA staff, “Saving the Medicare System with Medical Savings Accounts,” Policy Report No. 199, September 1995; John C. Goodman and Dorman Cordell, “The Nightmare in Our Future: Elderly Entitlements,” Policy Report No. 212, January 1998; Andrew J. Rettenmaier and Thomas R. Saving, “Saving Medicare,” Policy Report No. 222, January 1999; Mark E. Litow, “Defined Contributions as an Option in Medicare,” Policy Report No. 231, February 2000; John C. Goodman, Robert Goldberg and Greg Scandlen, “Medicare Reform and Prescription Drugs: Ten Principles,” Policy Report No. 256, October 2002; Andrew J. Rettenmaier and Thomas R. Saving, “Reforming Medicare,” Policy Report No. 261, May 2003; John C. Goodman, Devon Herrick and Matt Moore, “Ten Steps to Reforming Baby Boomer Retirement,” Policy Report No. 283, March 2006; Andrew J. Rettenmaier and Thomas R. Saving, “Medicare: Past, Present and Future,” Policy Report No. 299, June 2007; Andrew J. Rettenmaier and Thomas R. Saving, “A Medicare Reform Proposal Everyone Can Love: Finding Common Ground among Medicare Reformers,” Policy Report No. 306, December 2007.

2. Noah Meyerson et al., “The Long-Term Outlook for Health Care Spending,” Congressional Budget Office, November 2007.

3. In two separate studies for the National Center for Policy Analysis, Milliman & Robertson, Inc. estimate that Medicare spending plus Medigap premiums were sufficient to purchase insurance coverage for seniors comparable to what nonseniors typically enjoy, even without Part D (drug coverage) premiums and subsidies. Mark E. Litow (Milliman & Robertson), “Defined Contributions as an Option in Medicare,” National Center for Policy Analysis, February 4, 2000, and “Saving the Medicare System with Medical Savings Accounts,” National Center for Policy Analysis, Policy Report No. 199, September 1995.

4. Also, risk adjustment in the reformed system will be a bit more difficult because of the lack of a benchmark plan to guide the setting of subsidy payments. In the current system the benchmark plan is fee-for-service Medicare.

5. If the reformed Medicare insurance is less generous than the employer plan, the retiree may have to pay extra to join. Further, the firm may want to age- and risk-adjust the retiree’s share of the premiums to avoid younger employees subsidizing the retirees.

6. The insurer’s willingness to make a deposit will be based on expected reductions in spending as a consequence of the higher deductible.

7. “Designing Ideal Health Insurance,” in John C. Goodman, Gerald L. Musgrave and Devon M. Herrick, Lives at Risk: Single-Payer National Health Insurance around the World (Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield, 2004), pages 235-253.

8. Leslie Foster et al., “Improving The Quality Of Medicaid Personal Assistance Through Consumer Direction,” Health Affairs, Web Exclusive, March 26, 2003, pages w3-162–w3-175.

9. J.P. Newhouse, Free for All? Lessons from the Rand Health Insurance Experiment (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1994).

10. Thomas A. Massaro and Yu-Ning Wong, “Medical Savings Accounts: The Singapore Experience,” National Center for Policy Analysis, Policy Report No. 203, April 1996.

11. Shaun Matisonn, “Medical Savings Accounts in South Africa,” National Center for Policy Analysis, Policy Report No. 234, June 2000.

12. Greg Scandlen, “Medical Savings Accounts: Obstacles to Their Growth and Ways to Improve Them,” National Center for Policy Analysis, Policy Report No. 216, July 1998.

13. John C. Goodman, “Health Savings Accounts Will Revolutionize American Health Care,” National Center for Policy Analysis, Brief Analysis No. 464, January 15, 2004.

14. Devon M. Herrick, “Health Reimbursement Arrangements: Making a Good Deal Better,” National Center for Policy Analysis, Brief Analysis No. 438, May 8, 2003; and Devon M. Herrick, “Choosing Independence: An Overview of the Cash & Counseling Model of Self-Directed Personal Assistance Services,” Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Fall 2006.

15. Devon M. Herrick, “Consumer Driven Health Care: The Changing Nature of Health Insurance,” American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, forthcoming.

16. These reforms follow the proposal developed by John Goodman and Mark McClellan. See John C. Goodman, “Markets and Medicare,” Wall Street Journal, February 23, 2008.

17. John C. Goodman, “What Is Consumer-Directed Health Care?” Health Affairs, Vol. 25, No. 6, pages w540-w543. Note that telephone and email consultations as well as electronic medical records and electronic prescribing are far more prevalent in those medical markets where patients pay out-of-pocket, including walk-in clinics in drug stores and shopping malls, concierge doctor services and telephone consultation services provided by such companies as Teladoc. See John C. Goodman (with Michael Bond, Devon M. Herrick, Gerald L. Musgrave, Pamela Villarreal and Joe Barnett), Handbook on State Health Care Reform (Dallas, Texas: National Center for Policy Analysis, 2007).

18. John C. Goodman, “Markets and Medicare.”

19. John E. Wennberg et al., “The Care of Patients with Severe Chronic Illness: an Online Report on the Medicare Program by the Dartmouth Atlas Project,” Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care, Center for the Evaluative Clinical Sciences, Dartmouth Medical School, 2006.

20. Ibid.

21. Ibid.

22. Amy Hopson and Andrew J. Rettenmaier, “Medicare Spending Across the Map,” National Center for Policy Analysis, Policy Report No. 313, July 2008.

23. Reed Abelson, “In Bid for Better Care, Surgery with a Warranty,” New York Times, May 17, 2007.

24. Vanessa Fuhrmans, “A Novel Plan Helps Hospital Wean Itself Off Pricey Tests,” Wall Street Journal, January 12, 2007, page A1; Hoangmai H. Pham et al., “Redesigning Care Delivery In Response To A High-Performance Network: The Virginia Mason Medical Center,” Health Affairs, Vol. 26, No. 4, July 10, 2007, pages w532-w544.

25. Carole W. Cranor, Barry A. Bunting and Dale B. Christensen, “The Asheville Project: Long-Term Clinical and Economic Outcomes of a Community Pharmacy Diabetes Care Program,” Journal of the American Pharmaceutical Association, Vol. 43, No. 2, March 1, 2004, pages 173-184. Also see Angela Spivey, “Asheville Project,” Endeavors, University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill, Winter 2004.

26. An earlier Medicare prepayment proposal was presented in Andrew J. Rettenmaier and Thomas R. Saving, “Saving Medicare.” A more recent reform that combines prepayment with upfront cost sharing that is proportional to lifetime earnings is detailed in Andrew J. Rettenmaier and Thomas R. Saving, “A Medicare Reform Proposal Everyone Can Love: Finding Common Ground among Medicare Reformers.”

27. Since the rôle of government in the reformed system is to “top up” the amount of private savings and enrollee premiums to ensure that every senior will be able to enroll in an SCP, this means that government (and therefore taxpayers) will implicitly bear the risk associated with a diversified portfolio. That is, taxpayer burdens will rise in down markets and fall in up markets.

28. Estelle James and Augusto Iglesias, “Integrated Disability and Retirement Systems in Chile,” National Center for Policy Analysis, Policy Report No. 302, September 2007.

29. Note that with programmed withdrawals, the account owner’s right to the remaining funds continues to be contingent upon survival as well as the risk-rating scheme described below.

30. See the discussion of the incentives such an option creates in Estelle James, “Private Pension Annuities in Chile,” National Center for Policy Analysis, Policy Report No. 271, December 2004.

31. See, for example, John Cochrane, “Time Consistent Health Insurance,” Journal of Political Economy, January 1995.

32. Andrew J. Rettenmaier and Zijun Wang, “Explaining the Growth of Medicare: Part II,” National Center for Policy Analysis, Brief Analysis No. 408, August 6, 2002.

33. Devon M. Herrick, “Medical Tourism: Global Competition in Health Care,” National Center for Policy Analysis, Policy Report No. 304, November 2007.

34. We put aside a discussion of how this might work.

35. Seniors in Medicare fee-for-service are especially prone to receive care based on income. See Kanika Kapur et al., “Socioeconomic Status And Medical Care Expenditures In Medicare Managed Care,” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 10757, September 2004. Available at: http://www.nber.org/papers/w10757. Accessed February 12, 2008.

36. Put differently, the “top up” contribution from the government will be risk-adjusted, and it can be negative (a tax) if HIRA accounts become sufficiently large.

37. Jan J. Barendregt, Luc Bonneux and Paul J. van der Maas, “The Health Care Costs of Smoking,” New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 337, No. 15, October 9, 1997, pages 1,052-1,057; and Pieter H. M. van Baal et al., “Lifetime Medical Costs of Obesity: Prevention No Cure for Increasing Health Expenditure,” PLoS Medicine, Vol. 5, No. 2, February 5, 2008. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0050029. Accessed February 22, 2008.

38. Konstantin Magin, “Why Liberals Should Enthusiastically Support Social Security Personal Accounts,” Economists’ Voice, December 2007. Available at http://www.bepress.com/ev.

39. See the discussion in Rettenmaier and Saving, “A Medicare Reform Proposal Everyone Can Love: Finding Common Ground among Medicare Reformers,” describing the demand-side adjustments due to higher cost sharing. Supply-side responses are also estimated. Amy Finkelstein, “The Aggregate Effects of Health Insurance: Evidence from the Introduction of Medicare,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, February 2007. Finkelstein finds that as much as 50 percent of the real per capita health care expenditure growth between 1950 and 1990 can be attributed to the reduction in out-of-pocket spending. This estimate is significantly higher than the estimate that relies on the RAND HIE demand-side effects alone. See Appendix for the methodology.

40. Andrew J. Rettenmaier and Thomas R. Saving, “A Medicare Reform Proposal Everyone Can Love: Finding Common Ground among Medicare Reformers.”

41. The RAND simulation results on which the two methods are from Table 3.4, p.19, and Table G.2, pp. 104-105, of Willard G. Manning et al., Health Insurance and the Demand for Medical Care, RAND Corporation, February 1988, R-3476-HHS. Numerous caveats exist in applying the RAND results to the present case of Medicare. The demand responses among retirees due to different cost sharing arrangements may differ from the responses derived from the nonretired population on which in the RAND experiment is based. However, the RAND results provide the best available estimates.

42. Spending on Medicare covered services by age are derived from Medicare reimbursements by age using the most recent estimates of Medicare’s share of total spending on Parts A, B, and D.

43. The estimates in Rettenmaier and Saving, “A Medicare Reform Proposal Everyone Can Love: Finding Common Ground among Medicare Reformers,” are based on the demand-side responses and do not include anticipated supply-side responses.