Among the provisions of the recently enacted health law is a new federal program for long-term care. A variation of a proposal the Urban Institute dubbed "Medicare Part E," proponents say it is a sound insurance program paid for by the premiums of voluntary participants – claims that were once also made about Medicare.

Predictably, however, the new entitlement will add to unfunded federal obligations – the difference between government promises of future benefits and the revenues available to pay for them. Future attempts to shore up the program's finances by corralling more people into participation will only result in a greater unfunded liability.

Predictably, however, the new entitlement will add to unfunded federal obligations – the difference between government promises of future benefits and the revenues available to pay for them. Future attempts to shore up the program's finances by corralling more people into participation will only result in a greater unfunded liability.

The CLASS Act. The Community Living Assistance Services and Supports (CLASS) Act, passed as part of the "Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act," establishes a federal insurance program to provide benefits to workers who become functionally disabled – unable to perform normal activities of daily living, such as eating or bathing. For eligible workers and retirees, the CLASS program will pay some of the nonmedical expenses of long-term care, such as an aide to bathe them or prepare meals at home, or to defray some of the costs of nursing home care.

The program is voluntary, and will be funded by premiums paid by workers. Employers who choose to participate have the option to automatically enroll their employees and to deduct the premiums from their paychecks. Individual employees will be allowed to opt out, and those who work for nonparticipating employers will have the option to enroll individually.

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that average monthly premiums will start at $123 in 2011. After five years of premium payments, participants will be eligible for a projected benefit of about $75 per day ($27,375 annually), if they have at least two functional limitations, and a health care practitioner certifies the limitations are expected to last more than 90 days. They can receive the inflation-adjusted benefit for the rest of their lives, as long as the limitations remain.

A New Unfunded Liability. Nearly 10 million workers are expected to enroll in the CLASS program by 2019. The CBO estimates that the program will collect $41 billion in premiums during the first five years before it begins paying benefits. Over the first 10 years the government will collect about $72 billion more in premiums than the benefits it pays out.

If this were a private insurance program, the insurer would invest the premiums in stocks and bonds, and the return on those investments would pay for a substantial percentage of the eventual payouts. By contrast, the surplus CLASS funds will be spent on general government operations and replaced with IOUs from the Treasury. After the first 20 years or so, however, the CBO estimates that the program will begin to pay out more benefits each year than the premiums it collects. For every dollar by which benefits exceed current premium revenues, the federal government will have to tax or borrow another dollar. The unfunded liability will grow in following years.

The Problem of Adverse Selection. The CLASS program will charge premiums that are adjusted for the age, but not the health risks, of enrollees. This means that healthy individuals will pay higher premiums than are actuarially fair while those who are more likely to need benefits due to chronic conditions or unhealthy habits will pay less. As a result, the program can be expected to disproportionately attract high-risk participants while low-risk individuals will likely opt out. Because of this adverse selection, the program could begin running annual deficits sooner than the CBO predicts.

Medicaid versus Private Long-Term Care Insurance. More than 10 million Americans currently need long-term care services at home or in an institutional setting. Because long-term care insurance does not receive the same tax breaks as employer-provided health insurance, most people pay for it with after-tax dollars out of their own pockets. Due partly to the cost, only about 10 percent of individuals 50 years of age or older have private long-term care insurance.

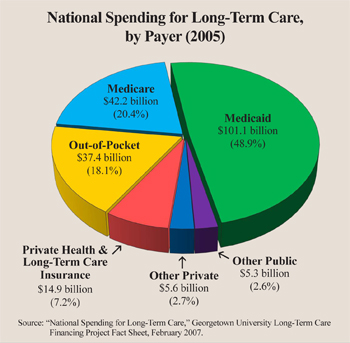

In fact, Medicaid, a joint federal-state program that is mainly for the poor, pays nearly half the cost of long-term care nationwide:

- In 2005 Medicaid paid for 49 percent ($101 billion) of all long-term care costs. [See the figure.]

- Of that total, $42 billion went toward home and community-based care while the remainder ($59 billion) paid for nursing home care.

- According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, just 7 percent of Medicaid enrollees received long-term care in 2002, but they accounted for more than half (52 percent) of total Medicaid spending.

The likelihood of needing long-term care services grows with age, but Medicare, the federal health program mainly for seniors, pays for only a limited number of nursing home days.

Conclusion. Proponents argue that the CLASS program will save Medicaid funds because care in the home is often less expensive than institutional care. Over the first 10 years, however, the CBO projects that Medicaid will save less than $2 billion.

As the CLASS program begins to add to the deficit, there will likely be calls to expand the pool of participants to include healthier populations that are less likely to use the benefits. However, the only way to get healthy people to participate in a program that overcharges them to subsidize the less healthy is to make the program mandatory.

Biff Jones is a graduate student fellow and Joe Barnett is director of policy research at the National Center for Policy Analysis.