One of the primary goals of the new federal health reform law – the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) – is to ensure that all Americans have health insurance. Yet it is generally overlooked that the proportion of Americans without health coverage has been relatively stable over time.

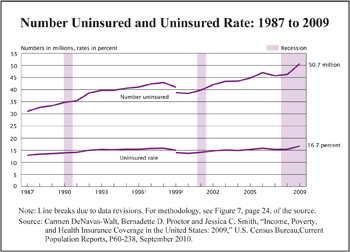

According to the Census Bureau, in 2009 the number of individuals lacking health coverage rose from 46.3 million to 50.7 million. The proportion of uninsured Americans rose from 15.4 percent to 16.7 percent mostly due to job losses.

In fact, the proportion of people without health insurance in 2009 is up just over one percentage point from a decade earlier. The increase in the number of uninsured over the past decade is largely due to the recession, population growth, immigration and individual choice. [See the figure.]

In fact, the proportion of people without health insurance in 2009 is up just over one percentage point from a decade earlier. The increase in the number of uninsured over the past decade is largely due to the recession, population growth, immigration and individual choice. [See the figure.]

How Serious Is the Problem? During the past 10 years the number of people with health coverage rose nearly 22 million, while the number without coverage at any point in time only increased about 5.3 million. The former is largely due to population growth, while the latter is largely due to a slowing economy. Typically, those who lack insurance are uninsured for only a short period of time – more than half will have coverage within a year.

In 2009, according to Census Bureau data, more than 83 percent of U.S. residents (253.6 million people) were privately insured or enrolled in a government health program, such as Medicare, Medicaid or the State Children's Health Insurance Programs (S-CHIP). An additional three million to six million people identified as uninsured may already be covered by Medicaid or S-CHIP but erroneously told Census Bureau they were uninsured because they do not associate Medicaid with insurance coverage. This is referred to as the "Medicaid undercount."

Who Are the Uninsured? The uninsured include diverse groups, each uninsured for a different reason:

Low-Income Families. Some 15.5 million uninsured adults and children live in households earning less than $25,000 annually. Many in this group qualify for Medicaid or S-CHIP but are not enrolled. Indeed, the Urban Institute estimates that two-thirds of uninsured children (4.7 million) qualify for S-CHIP or Medicaid but have not enrolled. It is often assumed that the uninsured are all low-income families. But among households earning less than $25,000, the number of uninsured is about the same as it was 10 years ago. However, 42 percent of this year's increase is in this group.

Just over 15 million uninsured residents live in households with incomes of $25,000 to $50,000 per year. Most in this group do not qualify for Medicaid and (arguably) earn too little to easily afford expensive family plans costing more than $12,000 per year.

Middle-Income Families. Nearly 20 million of the uninsured lived in households with annual incomes above $50,000 – over half of them (10.6 million) in households with incomes that exceed $75,000 annually. Arguably, many in this group could afford some type of health insurance – possibly a high-deductible plan or a plan with limited benefits.

Immigrants. About 13 million foreign-born residents lack health coverage – accounting for 26 percent of the uninsured. In 2009, 46 percent of foreign-born noncitizen residents were uninsured. Income may be a factor – but not the only one. Another factor may be that many immigrants come from cultures without a strong history of paying premiums for private health insurance.

Furthermore, only immigrants who have been legal residents for more than five years qualify for public coverage. Most of these will not qualify for health insurance subsidies once the health insurance exchanges are open in 2014. In 2007 about 7.3 million illegal immigrants were uninsured. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that illegal immigrants will compose one-third of the projected 23 million uninsured individuals in 2019.

The Young and Healthy. About 21 million 18-to-34–year olds are uninsured. Most of them are healthy and know they can pay incidental expenses out of pocket. Using hard-earned dollars to pay for health care they don't expect to need is a low priority for them.

Why the Nonpoor Are Uninsured: State Mandates. Government policies that drive up the cost of private health insurance may partly explain why millions of people forgo coverage. State-mandated benefits drive up the cost by requiring more coverage than consumers may want. Nationally about one-quarter of the uninsured have been priced out of the market by excessive state mandated benefits and mandated provider laws. In addition, many states try to make it easy for a person to obtain insurance after becoming sick by requiring insurance companies to offer immediate coverage for pre-existing conditions with no waiting period. Thus, when people are healthy they have little incentive to participate and tend to avoid paying for coverage until they need care.

Effect of Health Reform on the Number of Uninsured. The CBO estimates that about 32 million individuals will gain health coverage due to the PPACA – about half of whom will be covered by Medicaid. However, about 23 million people will remain uninsured in 2019 – nearly half the 50.7 million today. This figure may be wishful thinking. The penalties for forgoing health coverage are less than the cost of coverage ($695 per individual or 2.5 percent of income).

Furthermore, new federal regulations will require insurers to accept all applicants regardless of health status. An unintended consequence of this is that many will wait until they become sick to enroll in health coverage. In the short run, the PPACA may cause 1.4 million people to lose their limited benefit health plans, when new regulations implemented on September 23, 2010, will ban annual caps on benefits.

Conclusion. The PPACA is estimated to leave 23 million people without coverage and probably millions more will have difficulty accessing a doctor. More patients will be insured but that does not solve the problem of where they will be able to go to get care.

Devon Herrick is a senior fellow with the National Center for Policy Analysis.