Source: Health Affairs Blog

While President Barack Obama and congressional leaders continue to tussle over what to do about the nation’s unsustainable entitlement spending programs, the effects of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) seem to have gone largely unnoticed. This oversight is hard to explain.

In recent decades, real Medicare spending has been growing at a rate roughly equal to the rate of growth of real gross domestic product (GDP) plus two percentage points. That means Medicare has been growing at twice the rate of growth of national income — an obviously unsustainable path. The PPACA seeks to limit Medicare’s growth rate to the rate of GDP growth + one percent. This is the ultimate spending path assumed by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO).

However, the legislation also calls for additional productivity improvements which have the effect of lowering Medicare’s growth rate to GDP growth alone. This is the growth path assumed by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) in the most recent Medicare Trustees report. Since this report is an executive branch report and since the Secretaries of Labor, Health and Human Services and the Treasury are all Medicare trustees, we treat this report as reflecting the Obama administration’s view of its own health reform.

One way to think about this is to observe that if per-capita Medicare spending is growing no faster than the economy as a whole, it will ultimately grow no faster than the dedicated payroll and income taxes and premiums that fund it. In other words, if the PPACA can resist future legislative changes, once the baby boom generation works its way through the system the problem of Medicare spending will effectively be solved! The one caveat to this proposition is the role of continued increases in longevity on the ratio of workers to retirees.

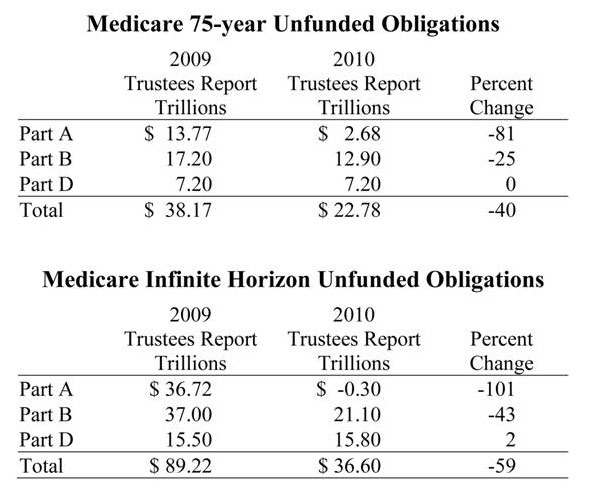

[Note: If the provisions of the PPACA are fully enacted, Medicare spending will be radically slowed by more than what is called for in the Bowles-Simpson deficit reform commission report or in the separate proposals made by Paul Ryan and Alice Rivlin and by Pete Domenici and Alice Rivlin. But it will still grow faster than what is called for in the Ryan/House Republican budget.]The table below shows what the PPACA means in terms of Medicare’s unfunded liability. Prior to the passage of the PPACA, Medicare’s spending obligations minus expected premiums and dedicated taxes equaled almost $90 trillion — looking indefinitely into the future. Yet on the day that Barack Obama signed the health reform bill, that figure was more than cut in half!

Source:Andrew J. Rettenmaier and Thomas R. Saving, “Medicare Trustees Reports 2010 and 2009: What a Difference a Year Makes,” National Center for Policy Analysis, NCPA Policy Report No. 330, October 2010.

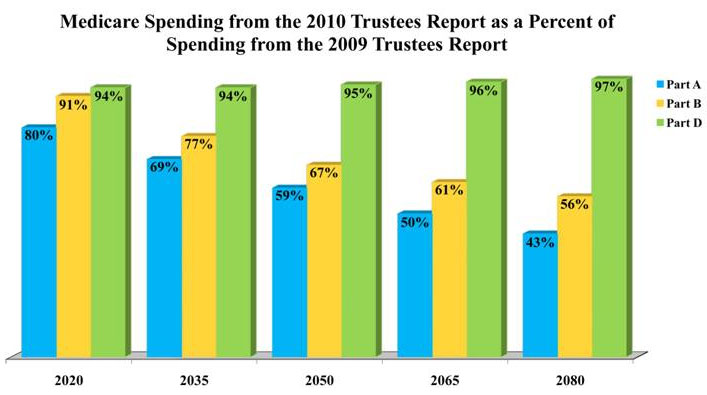

To get an idea of who the winners and losers are under reform, the graph below shows where the spending cuts will occur:

- By 2065, Medicare spending on hospital Part A services will be half of what it would have been under the old law.

- Medicare spending on doctors (Part B services) will be 61 percent of what it would have been under the old law.

- Yet remarkably, Medicare spending on drugs (Part D) will barely have changed at all.

Source: Table III.A2, 2009 and 2010 Medicare Trustees Report. Percents reflect the 2010 report’s shares of GDP as percents of the 2009 estimates.

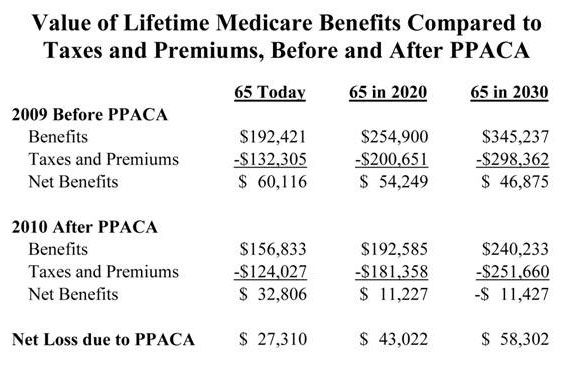

What do these projected changes in aggregate Medicare spending mean for individual retirees? Actually, that’s not clear. It’s much easier to say how much Medicare spending will change than it is to say what these changes will mean in terms of access to care. The table below shows the changes in Medicare spending for individuals of different ages:

- For someone turning 65 and enrolling in Medicare this year, the present value of projected Medicare spending was reduced by $35,588 the day Barack Obama signed the health reform bill.

- For 55-year-olds, the projected reduction in Medicare spending is $62,315 per person.

- For 45-year-olds, the loss totals $105,004.

Source: Courtney Collins and Andrew J. Rettenmaier, “How Health Reform Affects Current and Future Retirees,” National Center for Policy Analysis, NCPA Policy Report, forthcoming in 2011.

Getting A Handle On The Magnitude Of PPACA’s Payment Reductions

One way to think about these changes is to compare them to the average amount Medicare currently spends on enrollees each year. For 65-year-olds, the forecasted reduction in spending is roughly equal to three years of average Medicare spending. For 55-year-olds, the loss expected is the rough equivalent of five years of benefits; and for 45-year-olds, it’s almost nine years.

Consider other reforms that would have reduced Medicare spending by an equivalent amount of money. Rather than ratcheting down the amount that Medicare spends on the average beneficiary, suppose that Congress had raised the age of eligibility for the program instead.

The Medicare spending reduction called for in the health reform bill is the rough equivalent of raising the age of eligibility for 65-year-olds from 65 to 68. It is the equivalent of making 55-year-olds wait until they reach age 70 and 45-year-olds wait all the way to age 74!

Fortunately for beneficiaries, there are two offsetting benefits of lower Medicare spending. When Medicare spending declines (relative to trend) so do the required premiums and taxes needed to support those benefits. As a result, beneficiaries will have more disposable income than otherwise. However, this extra income will only equal about one-quarter of the spending reductions for 65-year-olds, about one-third for 55-year-olds and almost one-half of the spending reduction for 45-year-olds.

How does the PPACA accomplish the projected reduction in future spending on Medicare beneficiaries? Basically, it reduces the fees Medicare pays to doctors and hospitals, relative to what they would have been. Those fees are already well below what the private sector pays, however. For example, Medicare pays doctors almost 20 percent less than what private payers pay. It pays hospitals almost 30 percent less. In the future, that discrepancy will grow wider with each passing year.

To achieve the necessary targets, the new law gives an Independent Payment Advisory Board the power to recommend cuts in reimbursement rates for providers of health care. Congress must either accept these cuts or propose its own plan to cut costs as much or more than the panel’s proposal. If Congress fails to substitute its own plan, the board’s cuts will become effective. In this way, the growth rate for Medicare spending is officially capped. Moreover, the advisory board is barred from considering just about any cost control idea other than cutting fees to doctors, hospitals and other suppliers.

A primary factor in the projected cuts is the requirement that Medicare assume that health care providers will increase their productivity at the same rate as the non-health care sector, indefinitely into the future. However, this is something that has never happened in the past, largely because health is a labor intensive industry.

According to the Medicare actuaries, Medicare fees under the health reform bill will fall below Medicaid fees by the end of this decade — making seniors less desirable customers than even welfare mothers. By midcentury, Medicare will be paying less than half of what private payers pay and only 75 percent of Medicaid rates.

What Might PPACA’s Payment Reductions Mean To Beneficiaries?

What will these reductions in payments to health care providers mean in terms of out-of-pocket payments and access to care? Strangely, no one knows. But a reasonable assumption is that in order for seniors to have the same access to care they currently have they are going to have to offset some or all of Medicare’s spending reductions with additional spending of their own.

Some of the additional spending could come from the increase in disposable income generated by lower Medicare premiums and lower taxes. The remainder could come from reduced consumption of other goods and services.

Writing in Health Affairs, Harvard health economist Joe Newhouse notes that many Medicaid enrollees are currently forced to seek care at community health centers and safety net hospitals, and speculates that senior citizens may face the same plight in the not-too-distant future. Newhouse surmises that seniors who are able will turn to concierge doctors, paying out-of-pocket for services that Medicare won’t pay for. The current law stipulates that seniors cannot pay amounts in addition to Medicare fees when Medicare is paying the bill and doctors who accept higher fees can do so only if they leave the program. Providers are finding clever ways around these rules, however; and there will probably be increased political pressure to relax them.

The Medicare actuaries have also projected what these low payment rates would mean for the financial health of the nation’s hospitals. Overall, the actuaries predict that by 2019, one-in-seven facilities will become unprofitable and will probably be forced to leave the Medicare program. That number will grow to 25 percent of all facilities by 2030 and to 40 percent by 2050.

Basically, hospitals will not be able to provide seniors with the same kind of services they provide younger patients. To survive, we may see hospitals specialize in Medicare patients and provide far fewer amenities. In some cases, they may offer reduced access to expensive technology. A private room paid for by Medicare may be replaced by four- or six-bed wards. Menu choices may be replaced by the civilian equivalent of meals-ready-to-eat. Hospitals that accept Medicare patients may have access to MRI scanners, but not PET scanners.

For hospital services, as for physician services, providers can only cost-shift to other patients so much. If seniors are to get the same services other patients are getting, ultimately they are going to have to add on to Medicare’s reimbursement with out-of-pocket payments of their own.