Individual health insurance policies in New Jersey are among the most costly in the United States due to over-regulation and expensive mandates. Two radically different bills have been proposed recently to reduce the number of uninsured in the state by making health coverage more affordable. One proposal would mandate that individuals purchase insurance. It would also create a comprehensive, state-sponsored plan for those with incomes too high to qualify for Medicaid. The other proposal would allow New Jersey residents to purchase low-cost coverage from insurers licensed in other states.

Problem: Costly Insurance Regulations. One of the primary reasons people cite for their lack of health insurance is the inability to pay premiums. Yet, New Jersey's highly regulated health insurance market makes private coverage more expensive. Two insurance regulations that drive up costs in the state are guaranteed issue and community rating .

Guaranteed issue means that health insurance companies offering individual policies must sell coverage to all applicants, regardless of their medical condition. While this sounds like it protects consumers, it actually harms them by driving up prices. When insurers are forced to accept all applicants, they raise premiums to guard against losses. As a result, insurance becomes a poor value for everyone except those with serious health conditions, and people often wait until they become sick to buy coverage. Subsequently, insurance companies lose business and leave the market, and rates go up as competition diminishes. This has happened in all states that require guaranteed issue.

Community rating means that an insurer cannot adjust its premiums to reflect the individual health risk of consumers. This means everyone pays a similar premium; but, in reality, healthy people are charged more than they otherwise would be and sick people are charged less. Therefore, the majority who are healthy see their premiums rise to cover the risks and costs of other consumers.

A 2005 study by the Commonwealth Fund illustrates how insurance rates for young people are far higher in states with guaranteed issue and community rating than in states that do not have them. For instance:

- A healthy 25-year-old male could purchase a policy for $960 a year in Kentucky but would pay about $5,880 in New Jersey.

- A similar policy, available for about $1,548 in Kansas, costs $5,172 in New York.

- A policy priced at $1,692 in Iowa costs $2,664 in Washington and $4,032 in Massachusetts.

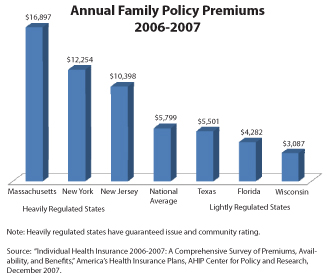

In states with guaranteed issue and community rating, premiums for family plans are also higher — often more than double the national average [see the figure]. Because of the higher cost, younger (or low-income) individuals with few health problems tend to drop insurance, leaving an increasingly unhealthy risk pool.

Proponents of guaranteed issue and community rating claim that rates will be affordable if everyone is required to have coverage. But this has not been the experience in Massachusetts, the only state with an individual mandate. Premiums have not fallen there.

Massachusetts will soon learn something else about mandates — they are difficult to enforce. For example, all but three states mandate auto insurance for drivers. Yet, in every state there are uninsured motorists. In fact, the proportion lacking auto insurance is usually within a percentage point or two of the number who lack health insurance. Enacting a nominal penalty, such as the loss of a standard tax deduction on a state income tax return, is unlikely to persuade young, healthy people to buy expensive health care coverage any more than penalties persuade uninsured motorists to purchase car insurance.

Problem: Costly Benefit Mandates. Forcing insurers to cover benefits that many consumers may not want (or need) also drives up premiums. For instance, New Jersey is one of only four states to mandate coverage for chiropody. And it is one of only 13 states that mandate coverage for in vitro fertilization — adding 3 percent to 5 percent to the cost of premiums. Proponents often argue that their particular mandate costs little; but when all 42 of New Jersey's mandated benefits are added together the costs are significant. Nationwide, as many as one-quarter of the uninsured may have been priced out of the market by costly mandates.

Wrong Solution: More Regulations. A proposal called the New Jersey Health Care Reform Act, authored by state Sen. Joseph Vitale, would force individuals to purchase insurance that many do not want or cannot afford. It would institute an individual mandate , requiring everyone to have health insurance. Low-income families would be enrolled in Medicaid, the State Children's Health Insurance Program (SCHIP) or given a subsidy to purchase coverage. Massachusetts is currently the only state with an individual mandate, but many states are considering similar plans.

Wrong Solution: State-Sponsored Commercial Insurance. Under the Vitale proposal, those with higher incomes would be required to purchase coverage from a private health insurer or enroll in a state-sponsored comprehensive, "commercial grade" insurance plan. The state plan would compete with commercial insurance and provide coverage similar to private group policies for small businesses. It is purposely designed to provide comprehensive benefits with limited cost-sharing by the people insured.

Vitale hopes a state-managed, comprehensive health plan could be administered more economically than private plans — his goal is to provide individual insurance policies for 75 percent less than private insurers currently charge. But there is little evidence this goal is within reach, and there are better ways to make insurance more affordable and cover the uninsured.

Right Solution: Allow Competition. A bill introduced by New Jersey Assemblyman Jay Webber, called the Healthcare Choice Act, would allow the state's residents to purchase lower-cost health insurance sold in other states. This would make coverage more affordable by injecting competition into the local market and by allowing residents to purchase insurance without New Jersey's expensive mandates. Consumers could shop for individual insurance on the Internet, over the telephone or through a local agent. The policies would be regulated by the insurer's home state. Consumers would be more likely to find a policy that fits their budget — giving more people access to affordable insurance. Moreover, competition across state lines would encourage state lawmakers to reduce costly insurance regulations.

Another Needed Reform: Block Grant Federal Funds. Instead of community rating and guaranteed issue, New Jersey should allow insurers to charge risk-based premiums. In order to cover residents too poor to afford private coverage, New Jersey could request a block grant for all federal Medicaid funds. This would give the state the flexibility to provide care in the most efficient way. For instance, the state could tailor its Medicaid benefits to meet the needs of different enrollees or subsidize employer health plans instead of charity care hospitals. In a system where most people have health insurance, the need for indigent care hospital subsidies should be low. Hospitals would compete for insured individuals' business by providing efficient care or patient-pleasing services.

Conclusion. Mandated benefits and regulations have driven up the cost of health insurance in New Jersey. Mandating health insurance would likely lead to a rise in the number of uninsured and an increase in the cost taxpayers must pay to subsidize their coverage. Conversely, deregulating the market to allow competition across state lines would make more affordable coverage available to more people.

Devon Herrick is a senior fellow and John O'Keefe is a junior fellow with the National Center for Policy Analysis.