The Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993 (FMLA) requires employers to allow employees to take 12 weeks of unpaid leave annually for a serious illness, to care for an immediate family member, or following an adoption or birth. The FMLA now applies to companies that employ 50 or more workers, but during the campaign President Obama supported expanding it to cover businesses with as few as 25 employees.

This would increase the number of workers covered from about 94 million (in 2005) to 107 million, according to estimates from the National Partnership for Women and Families. The president also proposed to expand the qualifying circumstances to include caring for an elderly family member or housemate, or following domestic violence or sexual assault, with up to 24 hours of leave each year for parents to participate in their children's academic activities.

The FMLA was enacted with good intentions: to help employees strike the right balance between their personal lives and careers without being penalized. Unfortunately, it adds to the cost of employment, reduces the ability of employers and employees to make flexible workplace arrangements, and makes small businesses less competitive in the marketplace. Expanding the FMLA will have many unintended consequences that will hurt, not help, working families. Working women will be particularly affected.

The FMLA was enacted with good intentions: to help employees strike the right balance between their personal lives and careers without being penalized. Unfortunately, it adds to the cost of employment, reduces the ability of employers and employees to make flexible workplace arrangements, and makes small businesses less competitive in the marketplace. Expanding the FMLA will have many unintended consequences that will hurt, not help, working families. Working women will be particularly affected.

The Cost of the FMLA. Businesses and their employees bear the cost of the FMLA. According to the Employment Policy Foundation, direct FMLA compliance costs totaled $21 billion in 2004. Specifically:

- The FMLA cost businesses $4.8 billion due to lost productivity, particularly intermittent leave for such activities as doctor's appointments;

- $5.9 billion for health benefits employers are required to continue providing employees on leave; and

- $10.3 billion to temporarily replace workers.

There are also indirect costs, including increased administration, litigation, record keeping and so on. Unpaid leave is part of an employee's total compensation. It substitutes for wages and other benefits. As with other noncash benefits, employees often absorb the cost of leave in the form of less take home pay.

Regulatory costs are typically much higher for small businesses than for large corporations, putting small firms at a competitive disadvantage. The Small Business Administration found that regulatory costs per employee are generally 45 percent higher for small firms, averaging $2,400 per worker. The higher cost of complying with federal leave policies reduces the competitiveness of small employers in attracting and retaining workers, because they are less able to provide the same level of wages and noncash benefits.

Currently, small business owners have an incentive to limit their workforce to fewer than 50 employees in order to avoid FMLA requirements. If firms with as few as 25 employees are forced to comply, at the margin some small businesses will not hire additional workers, some will reduce their workforce and some will shut their doors.

Small Business Leave Policies. Although there are differences between the regulated and unregulated sectors, the differences are not all that great. The Labor Department compared the leave policies of businesses with 50-99 employees (covered under the FMLA) to businesses with 25-49 employees. It found:

- About 60 percent of businesses with 25-49 employees provide unpaid leave for employee and family illnesses or a new child, while 82 percent of businesses with 50-99 employees do so.

- More than two-thirds (68 percent) of the smaller firms provide 12 weeks of unpaid leave for parents to care for a newborn versus 88 percent of the larger ones.

- Three-fourths of the smaller businesses provide 12 weeks of unpaid leave to care for a seriously ill family member versus 90 percent of larger businesses.

There are no significant differences between the two employer groups in the continuation of health benefits during leave. Businesses with 25-49 employees are only slightly less likely than those with 50-99 employees to provide leave for new and part-time employees. However, firms not covered by FMLA show more flexibility in providing leave for reasons beyond those guaranteed by the law. For example, smaller firms are more likely to allow additional leave for routine medical appointments than the FMLA-covered group.

The Institute for Women's Policy Research reviewed National Compensation Surveys to break down leave and other time off by firm size. It found that among businesses employing 25-49 employees, 67 percent offer paid sick days; 87 percent, paid vacation days; 35 percent, personal days (that is, general paid time off); 8 percent, paid family leave; and 77 percent, unpaid family leave.

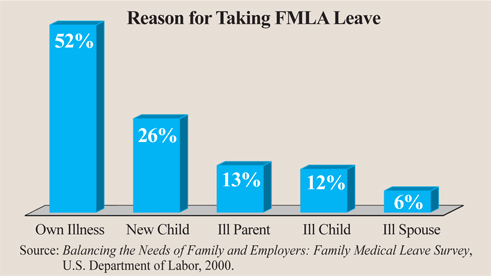

Impact on Women and Families. The U.S. Department of Labor has studied who takes FMLA leave, and why.

As the figure shows, people most often take leave as a result of their own serious illnesses. In 44 percent of the cases employees take leave to care for a newborn or adopted child or a sick family member. Leave-takers are 75 percent more likely to be married or living with a partner than other employees and 60 percent are more likely to have children living with them. Further, in instances where leave lasts longer than 30 days, family-related reasons far exceed any other circumstance.

Although women are slightly less than half of the workforce in the firms surveyed, they comprise 58 percent of employees taking leave, whereas men account for only 42 percent. Businesses prefer to hire the most productive employees at the lowest cost, and they don't want to pay higher employment costs than their competitors. Employers tend to avoid hiring individuals who will raise their costs. Thus, at the margin, businesses may avoid hiring women or tend to pay them less.

A Better Idea. Rather than relying on costly mandates like the FMLA, the government should consider policies that increase workplace flexibility. For instance, many employees would prefer to receive compensatory time off in lieu of overtime pay, but the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) requires overtime work to be compensated with time-and-a-half cash wages. This means that employees who work extra hours one week are unable to offset those hours with comp time in a subsequent week. Since the 1970s, federal and state employees have been allowed to substitute comp time off in lieu of overtime wages. Private sector workers should have similar options.

Expanding the FMLA to include very small businesses would be counterproductive because it would increase the cost of employment. Businesses are much less likely to make new hires and may actually be forced to eliminate jobs, especially those businesses around the 25-employee threshold of mandated FMLA coverage. Further, the increased costs of mandated leave could lead to a reduction of other employer-provided benefits such as health, retirement benefits or voluntarily-provided paid leave.

Terry Neese is a distinguished fellow, and Michelle Heinen and Daniel Wityk are research assistants with the National Center for Policy Analysis.