Most Americans are shielded from the full cost of health care and have little or no incentive to compare prices or choose lower cost providers. Indeed:

- On the average, patients pay only about 10 percent of the bill out of pocket when they visit their doctor.

- When patients are admitted to the hospital they pay only about 3 percent of inpatient costs directly – third parties, such as an insurer or the government, pay the rest.

However, when patients pay a significant percent of their health care costs, or benefit financially from choosing certain providers, they have a strong incentive to go where prices are lower. Thus, medical tourists go abroad for treatments that can cost up to 80 percent less than at home. Most of these patients are seeking medical treatments not typically covered by insurance (such as cosmetic surgery) or they are uninsured and pay out of pocket. However, they are also concerned about quality; thus, foreign facilities and physicians that cater to them typically meet U.S. standards.

Similarly, insured patients have an incentive to travel if their health plan requires them to do so or they face financial penalties – such as higher deductibles and copays – if they do not.

Here at home, health care providers often charge substantially different prices for medical procedures. This means there are opportunities to reduce costs by directing insured patients to a hospital across town or in another state, as well as overseas. But health insurers and employer health plans must identify providers offering quality services at lower prices and reward enrollees who use them.

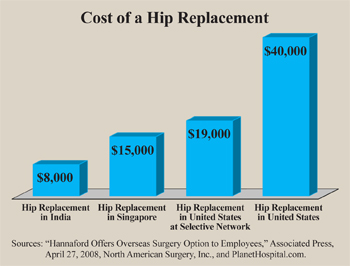

Competition through Medical Tourism. Domestic providers will compete on price if rivals offer lower prices. For example, Hannaford Brothers, a grocer based in Maine, offered employees hip and knee replacements with no out-of-pocket costs. However, the procedures were to be performed at National University Hospital in Singapore. For those who opted to travel, the company agreed to pay all transportation and medical costs, whereas cost-sharing could reach several thousand dollars if the procedures were performed locally. Consider [see the figure]:

- In the United States, an insurer might pay $40,000 for a hip replacement.

- In Singapore, hip replacements range from $10,000 to $15,000.

- A hip replacement in India would cost $8,000 or less.

After the announcement made headlines in many national newspapers, several U.S. hospitals agreed to steep discounts for such procedures.

Competition through Exclusive Networks. Some health insurers are already experimenting with small, exclusive networks – including Aetna, Cigna, WellPoint and UnitedHealth Group. These networks may have half the doctors and two-thirds as many hospitals as conventional networks. According to industry sources, exclusive networks can lower health insurance premiums about 15 percent.

This may require patients to travel some distance for certain procedures. For example, Lowe's home improvement stores recently offered employees free trips to Cleveland Clinic for cardiac surgeries in return for lower cost-sharing. Cleveland Clinic is world-renown for its low mortality after cardiac surgery. Nearly half (44 percent) of its heart surgery patients are not from Ohio.

This may require patients to travel some distance for certain procedures. For example, Lowe's home improvement stores recently offered employees free trips to Cleveland Clinic for cardiac surgeries in return for lower cost-sharing. Cleveland Clinic is world-renown for its low mortality after cardiac surgery. Nearly half (44 percent) of its heart surgery patients are not from Ohio.

Other provider networks are competing on price for the business of individuals, insurers and employer health plans:

- Colorado-based HealthBridge International offers U.S. employer plans a specialty network with flat fees for surgeries paid in advance that are 15 percent to 50 percent less than a typical network.

- North American Surgery, Inc., has negotiated deep discounts with 22 surgery centers, hospitals and clinics across the United States as an alternative to foreign travel for low-cost surgeries.

- North American Surgery's "cash" price for a hip replacement in the United States is $16,000 to $19,000. [See the figure.]

Lowering Costs through Exclusive Suppliers. Two U.S. hospitals in the same provider network may charge much different prices for the same procedure. In response to this price variation, some health plans are creating exclusive provider networks for certain procedures. This strategy, called selective contracting, lowers costs for two reasons: 1) Health plans are able to negotiate better prices with providers because they purchase large volumes of health services; and 2) Their bargaining power vis-à-vis providers is enhanced by the possibility that they will direct enrollees elsewhere, which encourages aggressive price competition.

Selective contracting is already commonly used by Pharmacy Benefit Management firms (PBMs) for employee health plans. The PBMs request bids from the makers of competing drugs within a class of drug therapies and the winning bidder may be guaranteed, say, 85 percent of the drug plan's business.

For instance, a PBM might ask the makers of the cholesterol medications Lipitor (Pfizer), Crestor (AstraZeneca), Lescol (Novartis), Vytorin (Merck/Schering-Plough) and Pravachol (Bristol-Myers Squibb) to submit bids to become the near-exclusive supplier of that drug type to plan members. If Pfizer submits the winning bid, Lipitor would be on the preferred drug list for all members prescribed cholesterol medications. The losing bidders might become nonpreferred suppliers for drug plan members that do not respond well to Lipitor. Enrollees using the preferred drugs face lower out-of-pocket costs. Enrollees have the right to take nonpreferred drugs, but are required to make significantly higher copayments.

Conclusion. Selective contracting with hospitals and clinics abroad, as well as at home, could foster greater competition among health care providers and lower health care spending. One obstacle is the new federal health care law. It caps the costs enrollees are required to pay in a given year. Currently, the limit is no more than $5,950 per individual or $11,900 per family. Cost-sharing limits should apply only to in-network providers. Without the ability to tightly control networks and reward enrollees who patronize these networks, hospitals and clinics are unlikely to compete on price.

Devon Herrick is a senior fellow with the National Center for Policy Analysis.