In most markets, prices and quality indicators are transparent – clear and readily available to consumers. Health care is different: Prices are difficult to obtain and often meaningless when they are disclosed. Many patients never learn the cost of their care.

The primary reason why doctors and hospitals typically do not disclose prices prior to treatment is that they do not compete for patients based on price. Prices are usually paid not by patients themselves but by third parties – employers, insurance companies or government. As a result, patients have little reason to care about prices.

And it turns out, when providers do not compete on price, they do not compete on quality either. In fact, in a very real sense, doctors and hospitals are not competing for patients at all – at least not in the way normal businesses compete for customers in competitive markets.

This lack of competition for patients has a profound effect on the quality and cost of health care. Long before a patient enters a doctor's office, third-party bureaucracies have determined which medical services they will pay for, which ones they will not and how much they will pay. The result is a highly artificial market which departs in many ways from how other markets function.

Among the services insurers typically do not pay for are:

- Integrated Care: Doctors offer fragmented services to diabetics, for example, but no one offers diabetic care as such – taking responsibility for the treatment of a patient's case from beginning to end.

- Patient Education: Diabetics, asthmatics and other patients with chronic conditions could manage much of their own care, if someone taught them how to do it.

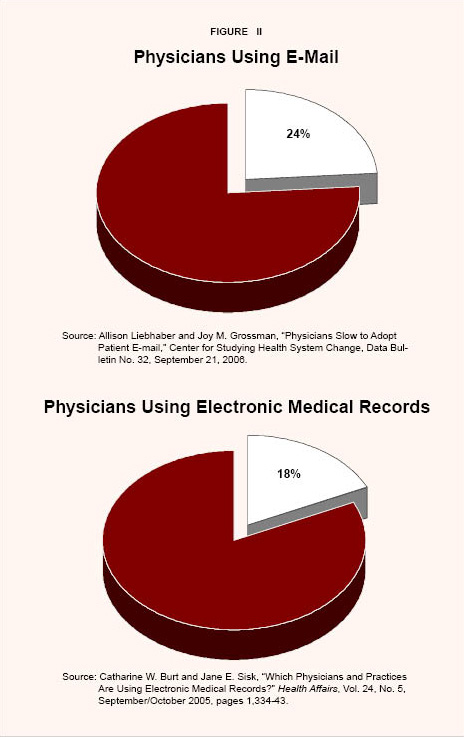

- Telephone and E-Mail Consultations: Potentially, the chronically ill could have more care, better care and less-costly care through modern communication devices – but few doctors consult by phone, and only one-in-four uses e-mail.

- Electronic Medical Records: Despite studies showing that electronic medical records can reduce costs and improve quality (by reducing errors, for example), only one-in-five physicians stores medical records electronically.

In health care markets where third-party payers do not negotiate prices or pay the bills, the behavior of providers is radically different. In the market for cosmetic surgery, for example, patients are offered package prices covering all aspects of care – physician fees, ancillary services, facility costs and so forth. Not only is there price competition, but the real price of cosmetic surgery has actually declined over the past 15 years – despite a six-fold increase in demand and enormous technological change. Similarly, the price of conventional LASIK vision correction surgery (for which patients pay with their own money) has fallen dramatically, even as procedures become more technically advanced.

Increasingly, cash-paying "medical tourists" are traveling outside the United States for treatment or surgery. In contrast to the typical American hospital stay, a package price includes all the costs of treatment, and often air fare and post-operative hotel accommodations. Prices are one-third to one-fifth as much as treatment at a U.S. hospital and the quality is typically high.

Retail walk-in clinics in drugstores, shopping malls and big-box retailers are another example. Originally established to bypass traditional health insurance, they post prices for procedures and minimize waiting times. They are staffed by nurse practitioners and use computer software to follow treatment protocols. Medical records are stored electronically and prescriptions can also be ordered online. The quality of care is often higher because the technologies used encourage best practices, improve care coordination, reduce errors and prevent adverse drug interactions.

Like walk-in clinics, a growing number of medical practices offer discounts for patients who pay bills directly and avoid third-party insurance. These entities almost always post their prices, and many store records electronically and offer e-mail and telephone consultations . Patients can also go outside their health insurance plan and arrange for telephone-based consultations with companies like TelaDoc Medical Services. A similar service, Doctor On Call , claims 70 percent of what physicians do can be done by phone! These services also store medical records electronically and "write" electronic prescriptions.

The marriage of the computer and telecommunications has also led to innovations that can increase economic efficiency and improve quality. Several new tools are now available to help physicians and patients find the most appropriate treatments using information on evidence-based protocols. Information on price and quality is available on the Internet to patients in some health plans. And objective, independent third parties often provide data for a fee.

The Internet is also transforming the market for prescription drugs. For example, when a patient logs on to Rxaminer.com and enters information about his or her prescription medications, the Web site produces a report including therapeutic and generic substitutes and over-the-counter alternatives for brand-name drugs. The drug-rating Web site AskAPatient.com lets patients compare experiences with drug therapies. Furthermore, ordering prescriptions online improves quality.

Patients paying with their own money can also use Internet services to order numerous lab tests on samples collected in convenient settings for fees that are nearly 50 percent less than tests ordered by physicians' offices.

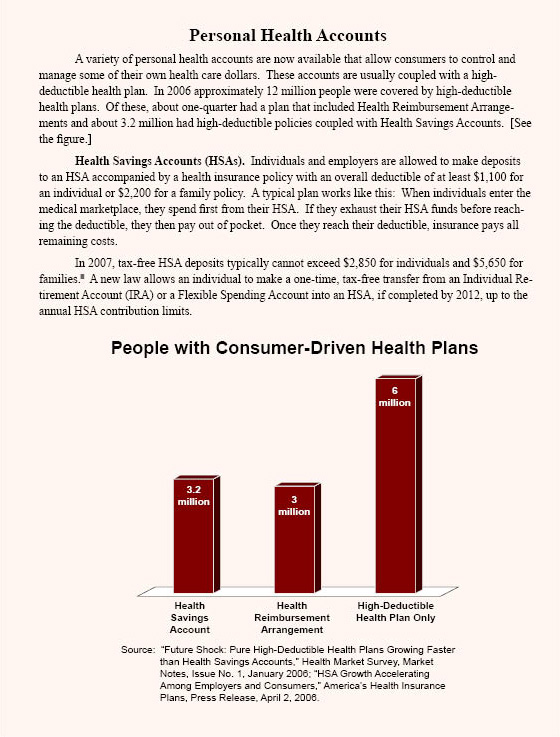

We are likely to see more of these challenges to traditional health care in the future. The reason? Increasingly, patients are paying more costs out of pocket. Deductibles for the average plan, for example, have nearly doubled over the past decade. And due to recent changes in the tax law, employees are increasingly managing their own health care dollars through personal health accounts, usually coupled with high-deductible health plans. In 2006, of the approximately 12 million high-deductible health plans, about one-quarter were accompanied by Health Reimbursement Arrangements (HRAs) and about 3.2 million were coupled with Health Savings Accounts (HSAs). This consumer-driven health care revolution gives individuals the opportunity to benefit financially from consuming health care wisely.

Although the medical marketplace is changing, legal, regulatory and cultural barriers to competition, innovation and transparency remain. For example:

- Medical societies and hospital trade associations have long tried to discourage price competition among their members; as a result, there is a cultural bias against advertising prices or competing on the basis of quality.

- Laws in many states restrict the practice of medicine to face-to-face encounters between physicians and patients, discouraging the use of the phone, e-mail and other innovative medical services.

- Potential lawsuits discourage physicians and hospitals from sharing information on medical errors and other quality indicators.

The biggest obstacle to transparency is a tax system that favors third-party insurance over individual self-insurance. For a middle-income employee, government is effectively paying almost half the cost of health insurance. This has encouraged consumers to use third-party bureaucracies to pay every medical bill.

Transparency is the natural product of a market in which patients control their own health care dollars and providers compete for those dollars. Thus, transparency will emerge as we fundamentally change the way we pay for health care. Some of these changes are already occurring, but government can speed the transition to greater transparency by removing obstacles to competition and innovation.

[page]Every day, millions of American consumers go shopping. They compare the prices and quality of goods and services ranging from groceries to cellular telephone service to fast food to housing. But there is one major sector of the economy where consumers typically do not make decisions based on comparison shopping, even though it accounts for one-sixth of the U.S. economy. That sector is health care.

“Patients typically do not know the cost of medical services in advance.”

A recent Harris Poll found that consumers can guess the price of a new Honda Accord within $300. But when asked to estimate the cost of a four-day hospital stay, those same consumers were off by $8,100! Further, 63 percent of those who had received medical care during the last two years did not know the cost of the treatment until the bill arrived. Ten percent said they never learned the cost. 1

In most markets, prices and quality indicators are transparent – clear and readily available to consumers. Health care is different: Prices are difficult to obtain and often meaningless when they are disclosed. Patients who ask for price information are likely to be disappointed. 2 Typically, neither the hospital nor the doctor will know the cost until the procedure is completed. Further, there is not one price for a procedure but many different prices. Each health insurer may have a different negotiated discount. And each enrolled patient entering the hospital may require a slightly different level of care. Of one hundred patients entering a hospital for the same procedure, no two may incur a bill for the same amount.

Furthermore, health care providers do not usually publish information on how their quality compares to other providers. Prospective patients have a legitimate interest in knowing about hospital-acquired infection rates, medical errors and surgical outcomes. Currently this knowledge is hard to come by. And what information is available is often technical and in a form that is meaningless to the average person.

It is odd that this nation of shoppers knows so little about price and quality in health care. This study will examine why that problem exists and what is being done about it.

[page]The primary reason why doctors and hospitals do not disclose prices in advance of performing services is that they do not compete for patients based on price. The reason: Patients rarely pay their own health care bills . Instead, they are paid by third-party payers. And, it turns out, when providers do not compete on price, they do not compete on quality either. 3

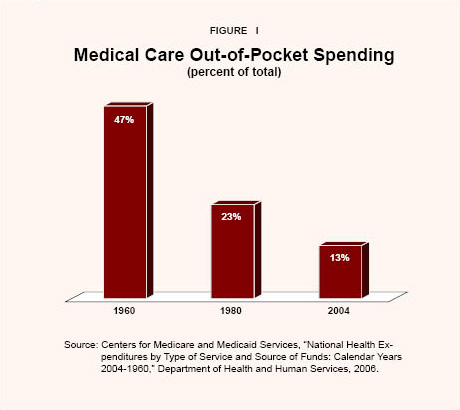

Because third parties – employers, insurance companies or government – pay most medical bills, patients often do not know or care what the price is. 4 As Figure I shows, the proportion of health care paid directly by consumers has been falling for decades: 5

- In 1960, consumers paid about 47 percent of overall health care costs out of pocket.

- The proportion had fallen by almost half to 23 percent by 1980.

- In 2004, consumers paid only 13 cents out of their own pockets every time they spent a dollar on health care.

The Market for Physician Services. On the average, every time American patients spend a dollar on physician services, they pay only 10 cents out of their own pockets. Millions of people do not even spend that much. Medicaid enrollees, Medicare enrollees with medigap insurance, and people who get free care from community health centers and hospital emergency rooms pay nothing at the point of service . And in most employer-provided plans, employees make only modest copayments for primary care services.

Since the services of physicians are a scarce and valuable resource, at a price of zero (or at a very low out-of-pocket price) the demand for these services far exceeds supply. In other markets, supply and demand are brought into balance through prices paid by consumers. Clearly, health care consumption is not rationed on the basis of price. Instead, people typically pay for physicians' services with their time, just as they do in other developed countries. According to a study in the American Journal of Managed Care , nearly half of patients must wait more than 30 minutes to see their doctor after arriving for an appointment. 6 And this is in addition to the time it takes to travel to and from the doctor's office.

“Consumers pay only a fraction of health care costs directly.”

Like money, time is valuable. So the higher the time cost to patients, the lower the demand will be for physicians' services. Thinking of market wages as a proxy for the opportunity cost of time (the next-best use of time), the cost of an hour of time is higher for a high-income patient than a low-income patient. Accordingly, physicians' practices in high-income areas need shorter waiting times to ration the same amount of care as practices in low-income ones. This suggests the longest waiting times of all will be for Medicaid patients and patients in hospital emergency rooms, where the money price is usually zero and people have a lower opportunity cost of time. 7

“The time of physicians is rationed by requiring patients to wait for care.”

The evidence appears to bear this "rationing by waiting" out. A recent survey found two-thirds of Medicaid patients were unable to obtain an appointment for urgent ambulatory care within a week. 8 Those who turn to hospital emergency rooms for their care find the average wait is about 222 minutes. 9

One consequence of rationing by waiting is that the time of primary care physicians is usually fully booked, unless they are starting a new practice or working in rural areas. This means almost all the physicians' hours are spent on billable activities. Further, there is very little incentive to compete for patients the way other professionals compete for clients. The reason: Neither the loss of existing patients nor a gain of new patients would affect the doctor's income very much. Loss of existing patients, for example, would tend to reduce the average waiting time for the remaining patients. With shorter waiting times, the remaining patients would be encouraged to make more visits. Conversely, a gain of new patients would tend to lengthen waiting times, causing some patients to reduce their number of visits. Because time, not money, is the currency patients use to pay for care, the physician doesn't benefit (very much) from patient-pleasing improvements and is not harmed (very much) by an increase in patient irritations.

The upshot is: When doctors do not compete for patients based on price, they do not compete on quality either. In a very real sense, they do not compete at all.

The Market for Hospital Services. In the opinion of most analysts, America has too many empty hospital beds. 10 Over the past decade or so, there has been a drastic decrease in the average length of stay and a steady movement from inpatient to outpatient services. 11 Under normal conditions, excess supply would signal a buyer's market – with sellers lowering prices, offering discounts and holding sales to shed their excess inventory. Hospitals, however, are not competing for patients based on price.

“Physicians typically do not compete for patients based on price or quality.”

Since doctors (rather than patients) more often choose the hospitals their patients enter, doctors are in essence the real customers of hospitals. But since doctors are not paying hospital prices (any more than patients are paying them), hospitals tend to compete for doctors based on the services and amenities doctors prefer. Having a surplus of beds and underutilized equipment (such as MRI scanners) means the system can easily adjust to the doctor's schedule rather than the other way around.

The analogue to patients waiting for doctors in a primary care setting is beds and equipment waiting for doctors in an inpatient setting. In neither case are prices allocating resources. And since prices do not ration resources, hospitals do not compete on the basis of price any more than doctors compete on price.

Moreover, as in the market for physicians' services, when there is no price competition there is no quality competition. In fact, as far as the patient is concerned, there is no competition at all.

[page]The lack of competition for patients has a profound effect on the quality and cost of health care. Long before a patient enters a doctor's office, third-party insurers have determined which medical services they will pay for and which ones they will not. They have also negotiated the fees. As a result, physicians have a financial incentive to provide services that will be reimbursed and to avoid any that will not. Physicians also have an incentive to provide those services that are generously reimbursed over those for which reimbursement is skimpy. The result is a highly artificial market which departs in many ways from how real markets function. The following are some examples.

Lack of Integrated Care. In normal markets, goods and services will naturally be bundled and priced to please the customer. But in health care, services aren't bundled and priced the way they would be if the medical marketplace even remotely resembled an efficient, competitive market. Care is fragmented among specialties and different providers, and communication among providers treating the same patient is often nonexistent. 12

Take diabetes, for example. Care tends to be delivered in discrete bundles, each with its own price. No single provider is responsible for desirable outcomes, such as fewer emergency room (ER) visits, lower blood sugar levels and so forth. This is because no one has bundled "diabetic care" as such – taking responsibility for final outcomes over a period of time in return for a fee. Because of the failure to bundle and price in sensible ways, costs are higher and quality is lower. 13

“Most insurers do not pay physicians to use e-mail or store medical records electronically.”

Most consumers take for granted that goods and services will be bundled and priced in customer-pleasing ways. The restaurant market, for example, is teeming with activity – almost continuously bundling and rebundling and pricing and re-pricing – all to attract and retain patrons. But suppose Blue Cross "negotiated" restaurant bundles and prices, making changes, say, every decade or so. Then going out to eat would be about as pleasant as a visit to the Department of Motor Vehicles.

Lack of Telephone and E-Mail Consultations. To get an answer to even the simplest medical question from a physician, patients must usually make an office visit. Lawyers and other professionals routinely communicate with their clients by telephone and by e-mail. They charge clients for the time, but clients are willing to pay for convenience. Few physicians communicate with patients that way – even for routine prescriptions. 14 [See Figure II.] The reason? Few health insurers pay physicians for telephone or e-mail consultations.

“Medical services are not bundled and priced in consumer-pleasing ways.”

Lack of Electronic Medical Records. Patients technically own their own medical records and have the right, at least in principle, to access them. But if they request a copy of their medical records, they are likely to receive a stack of smudged copies that includes illegible handwritten notes, undecipherable codes and obscure, abbreviated medical terminology. On their first visit to a medical practice, patients are required to fill out a medical history. Every time they are referred to a specialist, they are typically required to fill out similar forms again. But unless patients are in a managed care plan that emphasizes coordinated care or pharmacy benefit management, no one will compare their medical records for consistency and completeness or to detect the possibility of adverse drug interactions.

Manual record-keeping is inefficient and dangerous. It adds to administrative costs: An estimated $41.8 billion could be saved each year if medical records were stored electronically. 15 Handwritten prescriptions are also a major source of medical errors. Nearly 200,000 adverse drug events occur in hospitals each year because they don't have computerized physician order entry. 16 Furthermore, because most patients see a number of physicians over time, their medical records are fragmented and scattered. Assembling a complete record is time-consuming, often expensive and sometimes impossible.

Despite the capacity of electronic medical record (EMR) systems to improve quality and greatly reduce medical errors, less than one-in-five physicians and only one-in-four hospitals have such systems. 17 [See Figure II.] The reason? Few health insurers pay physicians to install or maintain EMR systems.

Lack of Efficient Care. In general, the historical increase in health care spending has led to improvements in medical services. 18 But a substantial proportion is spent on care that is apparently unnecessary or wasteful. For example, regions of the country with the best outcomes for Medicare patients with chronic conditions typically spend less per patient than regions that have worse outcomes. Compared to regions that use far more resources, patients in low-cost, high-quality regions such as Salt Lake City, Utah, Rochester, Minn., and Portland, Ore., are admitted less frequently to hospitals, spend less time in intensive care units and see fewer specialists. They also have lower mortality rates. 19

If every region provided care similar to the Mayo Clinic (in Rochester), one in every six dollars currently spent could be saved. If hospitals and physicians in every region in the country followed practice patterns similar to those in Salt Lake City, Medicare spending would be reduced by nearly one-third. 20

[page]

“Patients with traditional health plans are paying more out of pocket.”

In health care markets where third-party payers do not negotiate the prices or pay the bills, the behavior of providers is radically different. In these markets, entrepreneurs compete for patients' business by offering greater convenience, lower prices and innovative services unavailable in traditional clinical settings. Until recently, such markets were confined to the types of procedures health insurance doesn't cover, such as cosmetic surgery and vision correction surgery. Today, competitive markets are emerging outside the third-party payment system covering services ranging from primary care to major surgery. The reason: Patients are paying for more services out of pocket.

Tax law changes over the past few years have extended to individual self-insurance some of the same tax advantages traditionally enjoyed by third-party health insurance. Specifically, an increasing number of employees have personal accounts from which they pay medical expenses directly rather than rely on third-party insurance. This consumer-driven health care (CHDC) revolution gives individuals the opportunity to benefit financially from consuming health care wisely. 21 A recent Milliman survey of employers found that almost all (98 percent) are considering offering high-deductible health plans, up from less than half in 2003. 22 Many of these plans include personal accounts, such as Flexible Spending Accounts (FSAs), Health Reimbursement Arrangements (HRAs) and Health Savings Accounts (HSAs). [See the sidebar "Personal Health Accounts."]

“Prices are kept in check when patients pay for services themselves.”

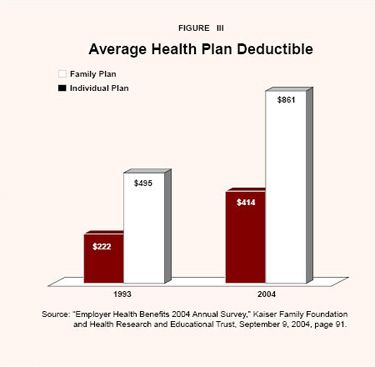

Even people with traditional health plans are increasingly asked to pay more out of pocket for their health care in the form of higher deductibles and coinsurance rates. 23 Deductibles for the average plan, for example, have nearly doubled over the past decade. 24 [See Figure III.] As a result of these changes, the number of people with a financial stake in the cost of their health care will continue to grow.

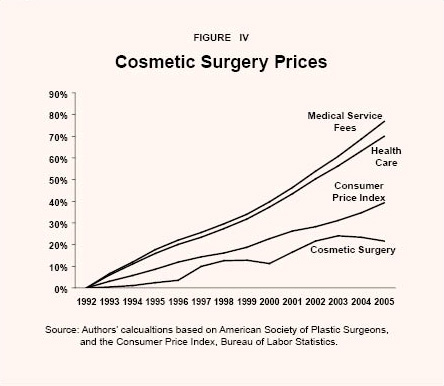

Case Study: Cosmetic Surgery. Unlike most other forms of surgery, cosmetic surgery is not covered by insurance. Patients must pay out of pocket. Physicians who perform cosmetic surgery know their patients are price sensitive. Thus, patients can typically (a) find a package price in advance covering all services and facilities, (b) compare prices prior to surgery and (c) pay a price that is lower in real terms than the price charged 10 years ago for comparable procedures, despite huge increases in demand and considerable innovation.

“The real price of cosmetic surgery has declined over time.”

- According to the American Society of Plastic Surgeons, there were 10.2 million cosmetic procedures in 2005, of which 1.8 million were surgical procedures, nearly six times the number performed in 1992. 25

- From 1992 to 2005, a price index of common cosmetic surgery procedures rose only 22 percent while the average increase for medical services was 77 percent; overall, prices for all goods increased 39 percent. 26 [See Figure IV.]

“Competition and innovation have led to lower-cost cosmetic procedures.”

The low prices, competition and easy access to information about price and quality found in the market for cosmetic surgery depend on several factors. First, when patients pay with their own money, they have an incentive to be savvy consumers. Second, as more people demand the procedures, more surgeons begin to provide them. Since almost any licensed medical doctor may obtain training and perform cosmetic procedures, entry into the field is relatively easy. Third, providers have become more efficient. Many have operating facilities located in their offices, a less-expensive alternative to outpatient surgery at a hospital. Further, absent are the gatekeepers, prior authorization and large billing staffs needed when third-party insurance pays the fees. Fourth, competition has led to lower prices and innovative substitute products. Take facelifts, for example: 27

- Surgical fees for facelifts increased less than 8 percent between 1992 and 2005 (which in real terms is a price reduction), according to data from the American Society of Plastic Surgeons.

- Cheaper, nonsurgical procedures designed to reduce the appearance of aging, such as laser resurfacing ($1,977), can replace or delay surgical facelifts in some patients.

- Retin-A treatments ($124), botox injections ($363), collagen injections ($390), hyaluronic acid ($557), chemical peels ($628), dermabrasion ($872) and fat injections ($1,174) are other, less-invasive alternatives that compare attractively to a facelift that costs $4,484 in surgeon's fees alone.

Case Study: LASIK Surgery . Competition and innovation are holding prices in check for vision correction surgery, which also is not usually covered by insurance. The cost per eye of conventional vision correction laser surgery (LASIK) averaged about $2,100 between 1999 and 2005. By 2005 the price had fallen to just over $1,600. 28 Competition from the newer, more-advanced Wavefront-guided LASIK helped drive down the price of conventional LASIK even further. Now conventional LASIK generally costs $200 to $300 less per eye than Wavefront LASIK. 29

Case Study: Retail Walk-In Clinics. Walk-in clinics are small health care centers located inside big-box retailers, or storefront operations in strip shopping centers. They are staffed by nurse practitioners and offer a limited scope of services but added convenience. 30 The pioneer of clinics operating within larger retailers, MinuteClinic, allows shoppers in Cub Foods, CVS pharmacies and Target stores to get routine medical services such as immunizations and strep tests. No appointment is necessary and most office visits take only 15 minutes. Most treatments cost from $49 to $59. 31 MinuteClinics clearly list prices, which are often only half as much as a traditional medical practice.

MinuteClinic uses proprietary software to guide practitioners through diagnosis and treatment protocols based on evidence-based medicine. In contrast to standard physician practice, medical records are stored electronically and prescriptions can also be ordered that way.

“Retail walk-in clinics give convenient, high-quality health care for half the price.”

While retail walk-in clinics are becoming more popular among consumers, some doctors oppose them. 32 They argue that physicians in traditional practices can spot potentially serious problems early and provide a level of comprehensive care not available in small clinics staffed by lesser-skilled nurse practitioners. 33

Yet there is evidence that the quality of routine care in walk-in clinics is comparable to treatment in traditional physicians' practices. MinuteClinics received high marks for quality of care in the recent Minnesota Community Measurement Health Care Quality Report. 34 The report measured appropriateness and quality of care for two common ailments among children: colds and sore throats. For example, in treating sore throats, each medical practice was evaluated on the basis of whether they administered a strep test and only prescribed antibiotics when test results were positive. 35 For appropriate care: 36

- MinuteClinics scored 100 percent.

- Mayo Clinics scored 74 percent.

- The average provider rating was 83 percent.

- The lowest provider score reported was 30 percent.

On care of children with colds: 37

- Mayo Clinics scored 93 percent.

- MinuteClinics scored 86 percent.

- The average provider rating was 86 percent.

- The lowest provider score reported was 24 percent.

MinuteClinics scored at least as well as the average and there was far less variation.

Many other entrepreneurs are launching similar limited-service clinics. Wal-Mart leases space for walk-in clinics to MinuteClinic and RediClinic (among others) in a number of stores and has begun to expand these operations nationwide. 38 RediClinic also allows patients to order numerous lab tests for fees that are nearly 50 percent less than tests ordered by physician offices. 39 Solantic is a small Florida-based chain of free-standing, walk-in urgent care clinics staffed by physicians who can provide a higher level of care than a clinic staffed by nurse practitioners. 40 Patients can register online and fill out their medical history prior to arriving at the clinic. Those who want X-rays or lab tests without a doctor's office visit can also sign up online. Initially, retail walk-in clinics did not accept insurance and many insurers were reluctant to cover the services. Today, a growing number of insurers cover the services, and more clinics accept insurance.

“Innovative health care services emphasize quality and convenience.”

Competition from these new clinics may lead traditional physician practices to offer more convenient weekend and extended hours. 41 Primary care would be more efficient if retail clinics could be integrated with traditional practices, so that patients could be treated in the lowest-cost setting. However, the federal "Stark laws" make it illegal for a clinic in which the physician has a financial interest to refer patients to that physician (a practice called "self-referral"). 42 It is also illegal for a physician to pay walk-in clinics to refer patients to him or to a hospital in which he has a financial interest.

Case Study: Telephone Consultations. TelaDoc Medical Services, located in Dallas, is a phone-based medical consultation service that works with physicians across the country. This service is designed for patients who urgently need a consultation but are unable to contact their primary care physician. Consultations are available around the clock, but patients must sign up in advance so their medical histories can be placed online.

When a patient calls TelaDoc, several nearby participating physicians are paged. The first physician to respond is paid for the consultation. TelaDoc guarantees a return call within 3 hours, or the consultation is free – but most calls are usually returned within 30 to 40 minutes. 43 Further, unlike most primary care practices, TelaDoc stores patient records electronically. The physician can access the patient's medical history online, e-mail a prescription to a pharmacy and add information to the patient's EMR. The use of these technologies improves care coordination and prevents adverse drug interactions.

Doctor On Call is a health information service that provides individual subscribers and health plan members with immediate telephone access to board-certified physicians. 44 According to Doctor On Call, patients often find it difficult to contact their regular physician by phone after hours. 45 With few options, people searching for peace of mind or reassurance (such as mothers of sick children) often turn to emergency rooms. In many cases, a phone call avoids an unnecessary ER visit.

Cash-Friendly Practices. Healthy Americans tend to visit the doctor a few times per year for short visits related to noncatastrophic conditions. As a result, they often over-pay for health plans that have first-dollar coverage for physician visits. An alternative is to self-insure for incidental medical needs, saving major medical insurance for catastrophic claims. A growing number of medical practices offer discounts for cash-paying customers or only accept direct (no third-party) payment. These providers are able to offer much lower prices because third-party payment imposes substantial overhead costs for billing, record keeping and claim filing.

SimpleCare, for example, is a physician association that requires patients to pay in full at time of service, but because their doctors do not need insurance billing departments, SimpleCare offers much lower prices. CashDoctor is a loosely structured network for physicians, dentists, chiropractors, pharmacies, laboratories, hospitals and out-patient facilities across the country that are "cash-friendly." CashDoctor is not affiliated with any insurance company or provider network. Practice styles and fee schedules are available online.

PATMOS EmergiClinic, in Greenville, Tenn., represents a growing trend toward cash-only practices. Founded by physician Robert S. Berry, it is a walk-in clinic for routine minor illnesses and injuries, open mornings Monday through Saturday and some afternoons by appointment. Established patients are occasionally treated via phone consultation. PATMOS EmergiClinic also uses electronic medical records and its physicians prescribe drugs electronically.

“Retail clinic patients know the prices they pay for services in advance.”

Prices for common medical treatments are posted for all to see. A poison ivy treatment costs $25. The price to treat sore throats is $35. Simple lacerations can be treated for $95. Fees are about half the price of what Medicare would pay. Most EmergiClinic patients do not have insurance; and physicians in traditional medical practice often don't want to see people who are not insured. 46

Medical Tourism. Increasingly, cash-paying patients are traveling outside the United States for surgery. Facilities that cater to such medical tourists typically offer: 1) package prices that cover all the costs of treatment, including physician and hospital fees, and sometimes airfare and lodging as well; 2) electronic medical records; 3) low prices that are often one-fifth to one-third the cost in the United States; and 4) high-quality care in facilities, and by physicians, that meet American standards.

Prices are so much lower that patients save money even with the added cost of travel. Most of the patients traveling abroad for surgery are uninsured or come from countries with long waiting lines for treatment. Insurers may make medical travel part of their provider networks in the future. 47 At least 40 company-sponsored health plans will begin offering overseas options through United Group Programs, a health insurer in Boca Raton, Fla. 48

While low-cost havens for plastic surgery have been popular for years, entrepreneurs in India and Thailand have recently built high-tech facilities to perform major surgeries, such as hip and knee replacements or cardiac surgery, specifically to attract medical tourists. 49 In addition to low prices, quality of care is emphasized.

PlanetHospital.com is a Web site that connects patients with high-quality medical facilities abroad. PlanetHospital's medical staff carefully screens potential clients to assess whether they are well enough to travel. Staff members then help clients choose appropriate physicians and destinations for care. Each patient's medical records are digitized and placed online to allow physicians in the destination country to easily review their medical history. PlanetHospital then arranges conference calls between potential physicians and the patient to discuss the procedure. Satisfaction is high – PlanetHosptial claims none of its clients have returned with a complaint about the quality of care or the surgery.

“Patients can travel abroad for surgery and pay a bundled price (including travel) that is one-third the cost in the United States.”

MedRetreat.com is another agency that arranges medical trips. Patients are assigned a U.S. program manager who helps them find appropriate destinations, procedures, hospitals and doctors. The package price typically includes airfare, lodging, hospital and physician fees. Once providers and services are selected, the patient's medical history is digitized and viewed by the physician. After a patient arrives in the country, a destination manager meets them and coordinates the medical service. After patients recuperate, the doctors release them to go home or to stay and see the sights. 50

The savings are significant. The price of an MRI in Brazil, Costa Rica, India, Mexico, Singapore or Thailand is $200 to $300 compared to $1,500 or more in the United States. A hip replacement can be performed in Argentina, Belgium, India, Singapore or Thailand for $8,000 to $12,000. 51 A herniated disc repair that would cost up to $90,000 in the United States is available for less than $10,000 in India – including airfare, hotel and meals. 52

"Millions of consumers have accounts that allow them to control some of their own health care dollars."

The marriage of the computer and telecommunications led to electronic mail and the Internet. As a result, the cost of information to the average consumer has fallen dramatically – and continues to drop. The resulting innovations are increasing economic efficiency and improving quality. Entrepreneurs of consumer-driven health care are taking advantage of these developments and are utilizing the Internet in ways that will revolutionize how health care is delivered. 53

General Medical Information. The growth of the Internet is leading to dramatic changes in consumer access to health care information. 54 In the past, most medical literature was available only at large libraries, medical schools or by subscription to expensive scholarly medical journals. Now, much of it is readily available to anyone with Internet access. 55 For instance, the United States National Institutes of Health placed its National Library of Medicine online for consumers to peruse. And WebMD.com, a commercial Web site, provides consumers with up-to-date information on diseases and treatments. Overall, there are approximately 20,000 health-related Web sites, 56 and about 80 percent of adult Internet users (or 93 million people) have searched for health information online. 57 This is a sharp break with the tradition of relying on doctors as the sole source for answers to health and medical questions. According to a 2002 survey of patients visiting an internal medicine practice, more than half used the Internet to gather health information. Of these, about six-in-10 rated what they found online "the same as" or "better than" the feedback they got from their doctors. 58

Information on Evidence-Based Protocols. In normal markets, sellers cater to customer requests for clear, concise information about quality. When objective evaluations are needed, independent third parties often provide data. 59 Several new Web-based tools are now available to help physicians and patients find the most appropriate treatment.

“Some Web sites offer information on treatment guidelines.”

MedEncentive is an Oklahoma-based firm that works with health plans to promote greater use of evidence-based, best-practice guidelines. The company provides health insurers with Web-based tools that both doctors and patients can use to identify recommended treatments, and gives both parties financial incentives to comply with them. Once physicians log on, patient treatment screens suggest a best-practice guideline for the diagnosed condition. Physicians who agree to follow the best practices (or provide a good reason for deviating) receive a higher reimbursement. They also receive more when they prescribe what is called "information therapy" to their patients – which may include having the patient read about procedures or protocols for taking medications or other treatments. 60 Once patients receive their prescriptions, they log on to a similar Web site that explains in lay terms the best evidence-based treatment. Patients who do so earn rebates that lower their out-of-pocket costs. According to MedEncentive, a recently completed year-long trial with several employers found participating firms reduced health care costs substantially, and both doctors and patients liked the program. 61

HealthDialog , a service offered through employee health plans, helps facilitate consistent use of evidence-based medicine by patients and doctors by providing personalized health coaching for chronic conditions and medical treatments. The goal is to encourage patients to take a more active role in the decision-making process and collaborate with their doctors to better manage chronic conditions. HealthDialog offers tools such as analysis of "unwarranted variation" from evidence-based protocols, based on academic research by John Wennberg from Dartmouth University: 62

- HealthDialog claims to reduce enrollees' health expenditure by 1 percent to 3 percent per year.

- Hospital admissions for a chronically ill, commercially insured population were reduced by 11 percent the first year and 17 percent the second year.

- Hospital admissions for Medicare patients were reduced 7 percent the first year and 11 percent the second.

- Surgeries deemed inappropriate by reviewers were reduced 20 percent to 40 percent.

Information on Prices. Some insurers are trying to remove the veil of secrecy that often surrounds health care costs. One example is Dallas-based insurer HealthMarkets, which offers Web-based decision support tools that allow enrollees to compare out-of-pocket costs online for 20,000 procedures performed by about 400,000 doctors nationwide. 63 Enrollees can use these tools to reduce their out-of-pocket costs. [See the sidebar "Using the Internet to Integrate Health Insurance and Consumer-Driven Health Care."]

Other health insurers are also taking steps to improve transparency – making price and/or quality information readily available to consumers. Aetna discloses on the Internet the prices it pays for common physician services in the Cincinnati area. It recently expanded this service to other cities and increased the number of procedures disclosed. Humana, UnitedHealth Group and other insurers are improving their Web-based tools to assist enrollees. 64

There are also Internet services that offer medical price information directly to all consumers. HealthGrades.com recently announced a plan to sell price reports online; consumers can look up the approximate cost of 42 different surgical procedures – ranging from vasectomies to gastric bypass surgery – across the country. 65

Quality Information. A few hospitals are posting quality information on their Web sites. For example, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center (DHMC) discloses its performance indicators for virtually all of the procedures and conditions it measures. DHMC also discloses the average costs of medical treatments and customer satisfaction ratings. 66 The Cleveland Clinic also discloses its quality indicators on a Web site. 67

“Some health insurers provide hospital and physician price and quality data to patients.”

Some health insurers are partnering with third parties to make quality information available to members. For instance, HealthMarkets, Lumenos and other health plans contract with medical information providers like Subimo to provide quality indicators on hospitals and clinics across the country in a Web-based, consumer-friendly format. On the Subimo Web site, each hospital's performance for a number of specific surgeries and treatments are rated in general terms (worse, average or better) compared to outcomes at hospitals nationwide. Health care quality metrics are still being fine-tuned (and are arguably still confusing for the layperson), but for each condition include complication and mortality rates. Additional quality indicators include the degree to which a hospital follows best-practices for treatment and prevention, and the level of technological services compared to the average hospital.

Subimo also reports the approximate number of procedures performed in each hospital compared to benchmarks for the volume of procedures considered necessary to keep skills sharp. Even if insurers do not make Web sites like Subimo part of their free Web-based services, consumers can access them directly by paying a nominal fee.

“Some Web-based services offer patients quality data.”

Medscape, owned by WebMD, recently created a Web-based hospital comparison tool called HospitalWise Professional . 68 HospitalWise Professional allows patients to view a variety of benchmarks for hospital quality, such as number of patients treated, mortality rates by procedure, major complications, number of days patients spend in the hospital and average hospital charges. 69 Medscape also has a directory that allows patients to sort physicians by travel distance, specialty, physician profile and/or hospital affiliation. In most cases patients can even request, reschedule or cancel an appointment online through this service. 70

A Department of Health and Human Services Web site tracks quality benchmarks at hospitals across the country. 71 There are indicators of treatment quality for four conditions: heart attack, heart failure, pneumonia and surgical care. The quality measures are based on the care recommended by the Hospital Quality Alliance (HQA), a collaborative effort of doctors, hospitals, federal agencies and health care accrediting organizations. To learn more about treatment quality for heart failure at a given hospital, for example, one can view data on the percent of patients who received an assessment of their left ventricular function; the percent given drug therapy for left ventricular systolic dysfunction; the percent given post-discharge care instructions; and finally, the percent of patients who smoke advised to stop smoking. If a patient selects an individual indicator, the Web site displays that hospital's rates compared to hospitals across the United States, other hospitals in the same geographic region and the average score for the top 10 percent of hospitals across the nation.

Patients themselves can help create one form of a quality indicator: Online forums for patient feedback. The Internet makes sharing experiences more convenient than ever. The Aetna Navigator Web site provides an easy way for enrollees to provide feedback on experiences with physicians. 72 The drug-rating Web site, AskAPatient.com, lets patients compare experiences with drugs therapies. 73 For instance, patients tend to rate antihistamines rather low. Antihistamines received an average score of only 2.6 out of a possible 5 points. By comparison, people rated Viagra 4.2 out of 5.

Shopping for Drugs. Patients' access to prescription drug prices and information has improved markedly over the past few years. Consumers can reduce the cost of some common drug therapies through the same techniques they routinely use when shopping for other goods and services. These include comparing prices, buying in bulk and looking for low-cost substitutes. Patients can also look for an over-the-counter or generic alternative or a therapeutic substitute in place of a high-priced, name-brand drug.

“Patients can lower drug prices using smart-shopping techniques.”

In some cases, patients may be able to buy medications in double-strength and split them in half. To find out about opportunities for lower-cost substitutes, patients can log on to Rxaminer.com and enter their prescription medications, prescribed strength levels and dose schedules. The Web site will produce a report that includes therapeutic and generic substitutes and over-the-counter alternatives for name-brand prescription drugs. The report explains the patient's options and can be printed out to discuss with a physician.

Armed with information about potential substitutes, a patient could then go to DestinationRx.com, a Web site affiliated with Rxaminer.com, to find the best prices for them at a number of highly competitive online pharmacies.

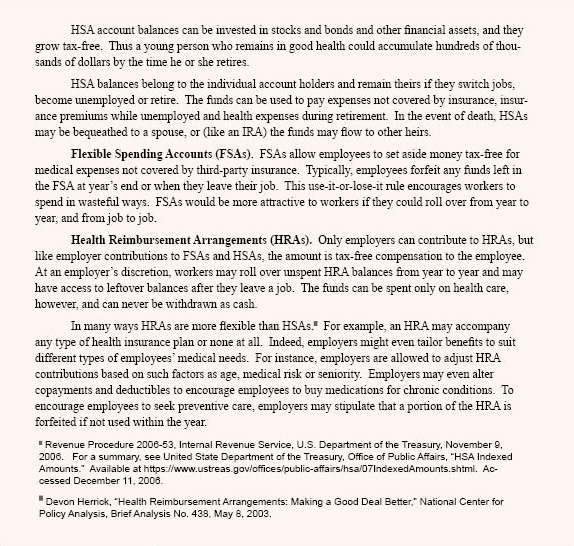

Case Study: Cardiovascular Drugs. Patients who pay for drugs out of their own pockets can save a lot of money by using the Internet. For example, patients prescribed 50mg of Tenormin daily can save money by comparison shopping for the best price and quantity. [See Table I.] For instance: 74

- The price of 100 doses (50mg) of Tenormin ranged from $155.66 at Drugstore.com to $125.49 Costco.com. 75

- Patients could save nearly 90 percent over the lowest-cost name-brand drug by switching to the generic alternative Atenolol; 100 doses of Atenolol ranged from $19.98 at Walgreens.com to $8.29 at Costco.com.

- Consumers could save another 15 percent – lowering the price from $8.29 to $5.65 – by splitting larger pills (100mg) in half.

Smart buying of this drug lowered the potential overall out-of-pocket cost by 96 percent – from a high of $155.66 to a low of $5.65.

“Patients can order diagnostic tests on the Internet.”

Online Savings for Seniors. DestinationRx.com's technology is also used on the Medicare.gov Web site to help seniors shop for a drug plan with the lowest annual out-of-pocket costs. Seniors can utilize another tool, called the Part D Optimizer, to find out if there are therapeutic substitutes on their plan's formulary that have lower out-of-pocket costs. The optimizer was designed specifically to help seniors avoid the coverage gap, or doughnut hole, in Medicaid Part D drug plans by finding the lowest prices. 76 [See the sidebar " Using the Internet to Lower Seniors' Drug Costs."]

Online Access to Laboratory Tests and Prices. Physicians usually don't offer patients options when ordering laboratory tests. But patients can gain by comparing the prices of different testing laboratories. Patients can even order some diagnostic tests on their own, without seeing a doctor. Storefront locations or walk-in clinics are beginning to offer affordable lab tests in a convenient setting, providing results quickly and without a visit to a physician's office. Here are a few Internet options:

- MyMedLab offers over 1,500 tests and sells bundled packages grouped by age, sex and family history. Prices are 50 percent to 80 percent lower than identical tests ordered by a physician, and a general health screen of 30 blood metrics costs about $45. Patients who order online save an additional 10 percent. 77

- Direct Laboratory Services, Inc. (DirectLabs.com) offers bundled blood tests for as little as $89, available at more than 5,000 collection centers nationwide. 78 Patients receive a thorough biochemical assessment of more than 50 individual tests including: cell count, thyroid profile, lipid profile, liver profile, kidney panel, profile of minerals and bone, fluids and electrolytes and tests on diabetes.

Some labs also sell genetic tests that can determine a patient's risk for cancer or heart disease. Prices for patient-ordered genetic testing for susceptibility to breast and ovarian cancer range from $586 for a single-point mutation to $3,312 for a complete sequence. 79

Patients can also order "virtual exams" using MRI or PET technologies to detect cancer, heart disease and other conditions. 80 Many physician groups oppose patient-ordered body scans for asymptomatic individuals because scans often yield ambiguous results that encourage patients to spend money on follow-up tests. 81 However, medical societies support doctor-ordered preventive screening for various conditions, at various ages, called for in medical protocols. Patients can order many recommended screening tests themselves, for less than a doctor would charge. The difference: Patients typically have to pay out of pocket for scans they obtain without a doctor's written orders, whereas their insurance typically covers physician-ordered tests. 82

[page]

As the preceding discussion suggests, the medical marketplace is changing. However, legal, regulatory and cultural barriers to competition, innovation and transparency remain. Following is a brief discussion of a few of them.

“Medical societies and trade associations have discouraged competition among providers.”

Regulations and Professional Culture Discourage Competition. The states have long licensed and regulated physicians with the ostensible goal of maintaining the quality of medical care. 83 However, state medical boards are dominated by physicians; and like the boards governing other regulated professions, they tend to be run for the benefit of practitioners. 84 In the past, these organizations tried to suppress competition among physicians by declaring certain practices unethical and subject to sanctions, such as denial of hospital privileges and even the loss of their license to practice medicine. 85 Advertising prices, for example, was once forbidden by ethical cannons and state laws. Even though these regulations and sanctions have been repealed or overridden by the courts, a cultural bias remains against advertising prices or competing on the basis of price.

Similarly, hospital trade associations have discouraged price competition for years; and the industry has always quietly discouraged quality comparisons. 86 Traditionally, hospital advertising tended to tout amenities, convenient locations or the number of doctors on staff – not the quality of medical care. 87

State Laws Discourage Innovative Medical Practices. There are also state laws that prevent medical practices from being organized in innovative ways.

Restrictions on the Employment of Health Professionals. Nurse practitioners can deliver some routine medical care without the direct supervision of a physician. However, some societies of physicians want to limit their independence by requiring the strict supervision – and even the physical presence – of a physician. A 2006 Florida law limits the number of retail clinics, staffed by nurse practitioners, a single physician may supervise to four. 88 This will effectively slow the growth of these efficient clinics. Georgia legislators attempted to limit the number of clinics a physician could supervise to three and the Missouri Legislature considered banning clinics inside pharmacies staffed only by nurse practitioners. 89

“Some states prohibit corporations from employing doctors.”

Restrictions on the Employment of Doctors. About one-third of states have enacted laws banning the "corporate practice of medicine," which prevents corporations from hiring physicians to practice on their behalf. 90 The implication is that a corporate employer might exert undue pressure to skimp on quality in order to increase or preserve profits. These laws ostensibly aim to ensure quality of medical care, but in practice they inhibit innovative service arrangements. 91 In some cases, this means a retailer, such as Wal-Mart, cannot open a health kiosk inside a store and hire practitioners to staff the clinic. However, corporations are generally free to lease space to companies that provide medical services by independent contractors. Subcontractors often have the same problem because they also cannot be controlled by a corporation.

One-third of the states have passed laws allowing some firms (such as hospitals and health plans) to hire physicians directly to practice on their behalf. In the rest of the states, the laws are either unclear or appear to support or restrict the practice to varying degrees.

Restrictions on Internet Medical Practices. While some restrictions on the practice of medicine have been removed in recent years, many still exist. For example, it is generally illegal for a physician in one state to consult with a patient online in another state without an initial face-to-face meeting. It is also illegal in most states for a physician who has examined a patient from another state to continue to treat the patient via the Internet. Unless the physician is licensed in the state where the patient resides, it is considered practicing medicine without a license. It may even be illegal in some states to consult with a patient online who resides in the same state as the physician; however, regardless of its legal status, many medical societies consider it unethical. 92

Restrictions on Collaboration between Health Care Providers. The federal "Stark laws" make "self-referral" illegal for a physician who has a financial interest in any clinics to which a patient is referred for treatment. It is also illegal for a physician to reward providers who refer patients to them or to a hospital in which he has a financial interest. Unfortunately, laws meant to prevent self-dealing and kickbacks also inhibit beneficial activities between doctors and hospitals. 93 For instance, the Stark laws could prevent a walk-in clinic from referring a patient with a chronic condition to an affiliated full-service practice. Likewise, a full service practice likely could not refer a chronic patient to a convenient walk-in clinic for simple services like blood test.

“Health professionals could be licensed nationwide.”

Liability Laws Discourage Disclosure of Error Rates and Other Quality Indicators. Health care providers are often reluctant to track quality indicators – including complications and infection rates – and do not want them available, lest the data be used against them in malpractice lawsuits. Public health experts who support the disclosure of quality indicators to improve quality say medical malpractice litigation is the "single most powerful force" that keeps data hidden." 94 In one survey, 76 percent of doctors said they had not disclosed a serious error to a patient out of fear that admitting an error could lead to a lawsuit. 95

[page]Some transparency advocates argue that doctors, hospitals and insurers must be compelled to fully disclose prices and quality measures. But the evidence suggests that where markets are competitive, transparency is a natural outcome. 96 In normal competitive markets, the role of government with respect to price and quality is mainly the prosecution of fraud. In health care, the greatest barriers to transparency, innovation and competition are government laws and regulations . Deregulating health care and equalizing the tax treatment of self-insurance and third-party insurance are important steps in the right direction.

Needed Change: Remove State Laws Restricting the Practice of Medicine. The courts have removed many anti-competitive restrictions on medical professionals, such as the prohibition on advertising, but the practices of physicians, physician assistants, nurses and technicians are still highly regulated. The most widespread limit on health care professionals is the requirement that they must be licensed by each state in which they practice. This means there are 50 state markets for health care, rather than one national market. This creates inefficiencies that increase costs and limit patients' access to care. For example, after Hurricane Katrina in 2005, thousands of doctors and nurses displaced to Texas were unable to legally treat evacuees until they received limited, emergency licenses from the state of Texas. Conversely, physicians, nurses and military-trained medics could not legally assist victims in Louisiana and Mississippi without special permission.

Insurers face a similar state restriction. Rep. John Shadegg (R-Ariz.) has proposed allowing health insurers licensed in any state to sell policies to the residents of any other state. The creation of a national market for health insurance would increase competition and thereby lower costs. Similarly, if physicians and other medical professionals licensed in any state were allowed to practice in any other state, labor markets for these professions would be more efficient and patients would have more treatment options. 97

Needed Change: Remove Laws Inhibiting Price and Quality Disclosure. Congress and the Federal Trade Commission should create a safe harbor that would allow providers to share prices with third parties without fear of violating antitrust laws. Though every gas station posts prices, it is not legal for hospitals and doctors to report prices to third parties that have any conceivable tie to a trade group.

Similarly, medical errors and other quality indicators that are reported to regulatory bodies should be freely available on Web sites and distributed to Web-content providers such as Subimo.com and HealthGrades.com. The opposition of hospitals and physicians to public disclosure of this information could be overcome if there were state and/or federal safe harbor laws preventing the use of self-reported medical errors in lawsuits. 98

While there is widespread agreement on the need for quality indicators in health care, there is much debate on what criteria to use. 99 Proponents of compelling health care providers to disclose prices have suggested that a federal regulatory agency should be established to define quality, collect the necessary data and audit health care providers to ensure the information is correct. Creating quality indicators that everyone can agree upon is problematic at best. Fortunately, there is an alternative to government-enforced quality standards. There is no reason that health care consumers should not be able to choose among competing standards or quality indicators, as they do in markets for other goods and services. For instance, there are many comparisons of automobile quality by independent, third-party organizations: J.D. Powers rates automobiles on customer satisfaction and breakdowns per unit of measurement (generally number of miles), Consumer Reports rates reliability and the Institute for Highway Safety performs crash tests on automobiles.

“Health care providers should be shielded from lawsuits when they voluntarily disclose errors.”

Needed Change: Remove State Laws Restricting the Corporate Practice of Medicine. The states should also repeal restrictions against the corporate practice of medicine. 100 Ownership is not restricted as much in other industries where very low error rates are required for safety. Take the airline industry. If airlines were prevented from hiring pilots and owning airplanes, the industry would likely be very different. Rather than numerous carriers flying thousands of large airliners across thousands of regularly scheduled routes, the industry would likely be dominated by charter pilots flying small propeller-driven planes.

Corporate ownership of airlines has not reduced safety. In fact, the health care industry is increasingly looking to quality improvement procedures in the airline industry for insight into ways to improve patient safety. 101 For instance, all flight crews receive training designed to break down the hierarchy that impedes communication by empowering all members of the crew to speak up in the event they feel safety is compromised. Many experts think the lack of communication among surgical staff in operating rooms leads to some preventable medical errors. 102

Corporate ownership also has the advantage of better access to capital markets, economies of scale and the ability to integrate the expertise of other professionals (such as industrial engineers).

Needed Change: Remove Federal Laws Restricting Collaboration among Health Care Providers. The federal Stark laws prohibiting self-referral should be modified to allow beneficial arrangements where care is coordinated and provided in a more efficient manner. Currently, a physician practice cannot recommend patients seek care in the most appropriate setting if the referring physician has a financial interest in the arrangement where the patient is being sent. With revised legislation, for instance, a traditional physician practice could offer integrated services, including disease management for chronic conditions, walk-in clinics for minor problems and discounted lab work.

“Federal health programs should make price and quality data readily available.”

Needed Change: Government Leading by Example. In markets where government is the primary third-party payer (Medicare, Medicaid and the Federal Employees Health Benefits Plan), policymakers can use existing technology to give enrollees access to price and quality information. Some modest steps in the right direction are already underway. President Bush gave this effort a boost by signing an executive order requiring the Departments of Health and Human Services, Defense, Veterans Affairs and the Office of Personnel Management to make significant strides toward increasing price transparency and encouraging patients to make more informed choices about their health care by January 1, 2007.

The executive order instructs the agencies to do four things: 1) develop and use interoperable technology to share electronic health information, 2) develop quality and efficiency standards for all doctors and hospitals who work with the agencies, 3) provide pricing information for health care services to all beneficiaries of each agency and 4) nurture relationships with providers who can deliver consumer-driven health care options to agency beneficiaries.

Considering that a quarter of Americans with health insurance are covered by the four agencies affected, President Bush is giving more than 60 million people access to information to make better health care choices. This sets an example for the private sector.

Needed Change: Remove Tax Penalties on Self-Insurance. Traditionally, the tax law has favored third-party insurance over individual self-insurance. Every dollar an employer pays for employee health insurance premiums avoids income and payroll taxes. For a middle-income employee, this generous tax subsidy means government is effectively paying for almost half the cost of health insurance. On the other hand, until recently the government taxed away almost half of every dollar employers put into savings accounts for employees to pay their medical expenses directly. The result was a tax law that lavishly subsidized third-party insurance and severely penalized individual self-insurance. This has encouraged consumers to use third-party bureaucracies to pay every medical bill, even though it often makes more sense for patients to manage discretionary expenses themselves. 103

“Tax laws should make it easier for people to self-insure for medical expenses.”

If the tax laws made it easier for people to self-insure instead of relying on third-party payers, competition would improve the efficiency of the medical marketplace. Currently, Health Savings Accounts (HSAs) are allowing millions of people to partly self-insure. However, congressional tax-writing committees have made decisions about the design of HSAs that more properly should be determined by the market 104 For instance, the amount of the HSA deposit and the accompanying health insurance deductible are set by law. Instead, the market should be allowed to answer such questions as: What is the appropriate deductible for which service? Should different amounts be deposited into the accounts of the chronically ill? In finding answers, markets are smarter than any one of us because they benefit from the best thinking of everyone. Further, as medical science and technology advance, the best answer today may not be the best answer tomorrow.

[page]Data on prices and quality are generally not available to patients in the U.S. health care system. That is because of the third-party payment system in which providers do not compete for patients based on price or quality. As a result, patients do not benefit from the price-reducing, quality-increasing activities that characterize competitive markets. To make prices and quality transparent in the health care marketplace, the way Americans pay for health care will have to change, and the health care industry will have to fundamentally change the way it does business. Some of these changes are already occurring because of the increase in individual self-insurance. In the prescription drug market, for example, transparency is already a reality for those who use the Internet. Government can speed the transition to greater transparency by removing obstacles to competition and innovation. But transparency does not have to be forced upon the health care industry. It will be the natural product of a market in which patients control their own health care dollars and providers compete for those dollars.

NOTE: Nothing written here should be construed as necessarily reflecting the views of the National Center for Policy Analysis or as an attempt to aid or hinder the passage of any bill before Congress.

[page]- Kathy Gurchiek, "Consumers Savvier about Cost of a New Car than a Hospital Stay," Human Resource News , August 2, 2005. Also see Tracey M. Budz, "Consumer Health Care Survey Reveals Mixed Bag of Results," Great-West Healthcare, Press Release, July 28, 2005. Available at http://www.greatwesthealthcare.com/C7/Press%20Releases/Document%20Library/Consumer_Survey_072805.pdf. Accessed April 6, 2006.

- Julie Appleby, "Ask 3 Hospitals How Much a Knee Operation Will Cost … and You're Likely to Get a Headache," USA Today , May 9, 2006.

- For a discussion, see John C. Goodman and Gerald L. Musgrave, Patient Power: Solving America's Health Care Crisis (Washington, D.C.: Cato Institute, 1992).

- Nearly 160 million Americans are covered through employer-sponsored health plans. See David Blumenthal, "Employer-Sponsored Health Insurance in the United States – Origins and Implications," New England Journal of Medicine , Vol. 355, No. 1, July 6, 2006, pages 82-88.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, "National Health Expenditures by Type of Service and Source of Funds: Calendar Years 2005-1960," Department of Health and Human Services, 2006. Available at http://www.cms.hhs.gov/NationalHealthExpendData/downloads/nhe2005.zip. Accessed January 2006. Also see Katharine Levit et al., "Trends in U.S. Health Care Spending, 2001," Health Affairs , Vol. 22, No. 1, February 2003, pages 154-64.

- James P. Meza, "Patient Waiting Times in a Physician's Office," American Journal of Managed Care , Vol. 4, No. 5, May 1998.

- John C. Goodman, "Time, Money and the Market for Drugs," National Center for Policy Analysis, Special Publication, December 5, 2005.

- Surveyors called potential medical providers, including physicians and clinics, posing variously as Medicaid, uninsured or insured patients seeking an appointment for specific conditions and symptoms considered medically urgent. Attempted access was considered successful when the caller was able to schedule an appointment within seven days. The surveys were conducted in major, geographically dispersed urban areas. See Brent R. Asplin et al., "Insurance Status and Access to Urgent Ambulatory Care Follow-up Appointments," Journal of the American Medical Association , Vol. 294, No. 10, September 14, 2005, pages 1,248-54. Also see Jae Kennedy et al., "Access to Emergency Care: Restricted by Long Waiting Times and Cost and Coverage Concerns," Annals of Emergency Medicine, Vol. 43, No. 5, May 2004, pages 567-73.

- Ken Fuson, "‘Patient' Says It All," USA Today, May 31, 2006.

- By the mid-1990s, bed occupancy at community hospitals had fallen below 60 percent. See Bernard Friedman, "Commentary: Excess Capacity, a Commentary on Markets, Regulation, and Values," Health Services Research , Vol. 33, No. 6, February 1999, pages 1,669-82. Keeler and Ying estimated the cost of excess capacity at $25 billion in 1993; see Theodore E. Keeler, John S. Ying, "Hospital Costs and Excess Bed Capacity: A Statistical Analysis," Review of Economics and Statistics , Vol. 78, No. 3, August 1996, pages 470-81.

- For a description of hospital capacity and the move to outpatient treatment, see "Statement of the American Hospital Association Submitted to the Federal Trade Commission," March 25, 1996. Available at http://www.ftc.gov/opp/global/amhospas.htm. Accessed December 18, 2006.

- In fact, due to Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) privacy regulations, it's often illegal for providers treating the same patient to discuss the patient's condition without expressly given patient consent.

- Michael E. Porter and Elizabeth Olmsted Teisberg, Redefining Health Care: Creating Value-Based Competition on Results (Boston, Mass.: Harvard Business School Press, 2006).

- Christine Wiebe, "Doctors Still Slow to Adopt Email Communication," Medscape Money & Medicine, Vol. 2, No. 2, 2001.

- Richard Hillestad et al., "Can Electronic Medical Record Systems Transform Health Care? Potential Health Benefits, Savings, and Costs," Health Affairs , Vol. 24, No. 5, September/October 2005, pages 1,103-17.

- Ibid.

- Catharine W. Burt and Jane E. Sisk, "Which Physicians and Practices Are Using Electronic Medical Records?" Health Affairs , Vol. 24, No. 5, September/October 2005, pages 1,334-43.

- David M. Cutler, Your Money or Your Life: Strong Medicine for America's Health Care System (New York, N.Y.: Oxford University Press, 2004).

- John E. Wennberg et al., "The Care of Patients with Severe Chronic Illness: An Online Report on the Medicare Program," Center for the Evaluative Clinical Sciences, Dartmouth Medical School, 2006. Available at http://www.dartmouthatlas.org/atlases/2006_Chronic_Care_Atlas.pdf. Accessed December 15, 2005.

- Ibid.

- As of January 2006, 3.2 million people had HSAs. "January 2006 Census Shows 3.2 Million People Covered by HSA Plans," America's Health Insurance Plans, Center for Policy and Research, March 9, 2006. An additional 3 million had HRAs while 6 million had a high-deductible health plan without a personal health account.

- See "Healthcare Coverage; Insurance Company Launches New Health Plans and Health Savings Accounts," Managed Care Weekly Digest , February 28, 2005.

- Kimberly Blanton, "Putting a Premium on Healthy Behavior," Boston Globe , February 17, 2005.

- For instance, coverage by Physician Provider Organizations (PPOs) rose from 27 percent to 58 percent of all employees in group health plans over the past 10 years, and 31 percent of PPOs used by small employers now feature in-network deductibles of $1,000 or more. "U.S. Health Benefit Costs Rises 7.5% in 2004, Lowest Increase in Five Years," Mercer Human Resource Consulting, Press Release, November 22, 2004; "Employer Health Benefits 2004 Annual Survey," Kaiser Family Foundation and the Health Research and Educational Trust, September 9, 2004.

- Ibid.

- American Society of Plastic Surgeons and the Consumer Price Index, Bureau of Labor Statistics.

- See "2005 Average Surgeon/Physician Fees: Cosmetic Procedures," American Society of Plastic Surgeons, 2006; and "1992 Average Surgeon Fees," American Society of Plastic Surgeons, 1993.

- Data from Market Scope, LLC. See "Lasik Lessons," Wall Street Journal , March 10, 2006.

- Liz Segre, "Cost of LASIK and Other Corrective Eye Surgery," AllAboutVision.com, July 2006. Accessed July 21, 2006.

- Milt Freudenheim, "Attention Shoppers: Low Prices on Shots in Clinic," New York Times , May 14, 2006.

- Information taken from MinuteClinic.com Web site. Accessed November 16, 2006.

- For example, see J. Edward Hill (President, American Medical Association), "AMA to Tennessean: MinuteClinics Not Providing Patients with Quality Health Care," The Tennessean , Letter to the Editor, September 15, 2005.

- Some physicians already employ nurse practitioners (NPs) to see patients needing routine services. NPs work under the (nominal) supervision of physicians – who often pay them a salary and bill for their services.

- Minnesota Community Measurement, "2006 Health Care Quality Report." Available at http://www.mnhealthcare.org/~main.cfm. Accessed November 16, 2006.

- For sore throat scores, see http://www.mnhealthcare.org/~Display.cfm?measure=7. Accessed January 5, 2007.

- Ibid.

- For cold scores, see http://www.mnhealthcare.org/~Display.cfm?measure=6.

- Rik Kirkland, "Wal-Mart's RX for Health Care," Fortune , April 17, 2006. RediClinic is venture of AOL founder Steve Case's Revolution Health Group and the company Interfit.

- Information taken from RediClinic Web site.

- Information obtained from Solantic.com Web site. See also Milt Freudenheim, "Attention Shoppers: Low Prices on Shots in Clinic," New York Times , May 14, 2006.

- Maureen Glabman, "What Doctors Don't Know About the New Plan Designs," Managed Care Magazine , January 2006.

- Named after their chief proponent Rep. Pete Stark (D-Calif.). For an analysis of the Stark laws, see Jo-Ellyn Sakowitz Klein, "The Stark Laws: Conquering Physician Conflicts of Interest?" Georgetown Law Journal , November 1998.

- Information obtained from conversations with TelaDoc executives in addition to the TelaDoc Web site.

- Conversations with Arthur Stern, corporate marketing specialist at Doctor On Call and the Doctor On Call Web site.

- This is probably because physicians are not reimbursed for phone calls. Doctors often have busy schedules requiring long hours. Physicians' time is a scare resource so they use what time they have to perform the tasks that pay versus those that do not pay. See John C. Goodman "Time, Money and the Market for Drugs," National Center for Policy Analysis, Special Publication, December 5, 2005. Available at http://www.ncpathinktank.org/pub/special/20051205-special.html.

- Robert S. Berry, "Testimony of President and CEO of PATMOS EmergiClinic, Inc., Greeneville, Tennessee," Joint Economic Committee of Congress, April 28, 2004.

- Mercer Health & Benefits predicts this will be the case. See Judy Foreman, "Bon Voyage, and Get Well!" Boston Globe, October 2, 2006.

- Joe Cochrane, "Why Patients Are Flocking Overseas for Operations," Newsweek International , October 30, 2006.

- Devon Herrick, "Medical Tourism Prompts Price Discussions," Heartland Institute, Health Care News , October 1, 2006.